A couple of weeks ago, Paula and I bought a small solar telescope. It just kinda happened.

Paula became very interested in getting a solar telescope several years ago when she had a chance to look through one and got to see solar prominences live and up close for the first time. I was less enthusiastic; many years ago I did solar astronomy professionally, so my standards for what constitutes a decent image are, well, a tad unrealistic. I doubted I'd be satisfied with low-cost gear. $10,000 or $20,000 will buy you research-grade equipment, but that's not exactly in my price range!

The Orion Telescope store in Cupertino announced an open house where they'd be showing off the Coronado line of solar telescopes. The technical specifications for low-cost scopes were not encouraging—small aperture and wide bandwidth are not conducive to serious viewing. Still, I was curious to see what the view was like through these low-end instruments. Then I could better figure out what level of unaffordable scope might make me happy.

To my surprise, I found I enjoyed the view through even the smallest and cheapest Coronado PST ("Personal Solar Telescope") (figure 1). On top of that, the price had dropped from $599 to $499. Paula and I looked at each other, shrugged, and decided we could always call it an early Xmas present (a blatantly transparent rationalization).

The PST has a 40mm aperture, a 400mm focal length, a 1 Ångstrom filter bandpass, and weighs 3 pounds. It's got a standard tripod socket on the base, so I just mounted it on my Bogen tilt-pan head trpod. For a scope this small, you don't need anything that fancy; pretty much any 'pod you've got lying around will do.

The PST comes with a 20mm eyepiece. That's entirely insufficient for solar viewing, except for the very largest (and rare) prominences and sunspot groups. A 10mm eyepiece is a much better choice as a standard. Normally I use a 7mm; if the seeing isn't good enough to support the 7mm eyepiece, it's pretty poor seeing. Which means that unless something really interesting is happening, I don't care. With good seeing I go down to 5mm, easy. With great seeing, 3mm. You don't need to buy expensive eyepieces: four-element Plössls are fine. With careful shopping, you should be able to pick up three for around $100.

There are some tricks to using a scope like this. The first is getting it pointed towards the sun. Swing the scope around until the shadow of the front hood or the adjustment ring is centered on the body of the scope (figure 2). Then tilt the scope up and down to align the sun's image in the bore sight (figure 3). The bore sight may not be perfectly aligned, and the proper position for the Sun image may not be dead center. When you find the proper position for the image, mark that spot on the ground glass of the sight with a sharp marking pen. Makes keeping the scope pointed a lot easier!

If you're using a tilt-pan head, tilt the scope so that the eyepiece is horizontal instead of vertical. The highly collimated, monochromatic light projected by the eypiece makes every damned floater in your eye clear as crystal. Keeping your head vertical keeps the floaters drifting a bit more and makes it easier to see the solar image. You'll still have to take breaks and move your head and eyes around to stir things up inside your eyeball.

What will you see? A deep crimson red sun, dappled with just-barely-visible granularity. The image will be dim. The telescope throws away more than 99.99% of the light! On almost any day, even in this period of low solar activity, you'll see small prominences around the rim. They change in a matter of hours or less. Solar astronomy like watching the weather. From minute to minute, the view will slowly change. We leave the scope set up in the living room and take it outdoors a couple of times a day, just to see if anything interesting is happening. Usually there is.

If you're lucky, there will be a sunspot group, which means there will be bright flares and dark filaments against the surface of the sun.

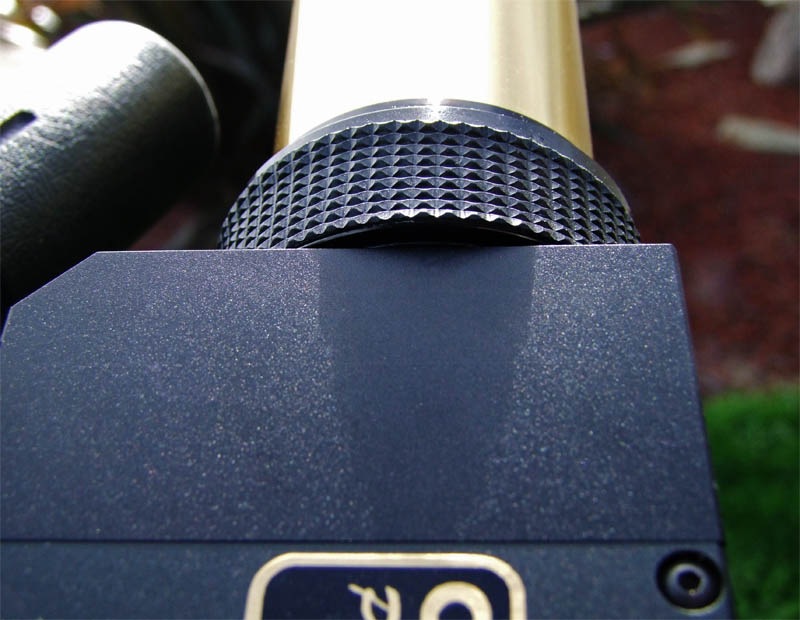

For reasons of space, I'm not going to explain how the H-Alpha hydrogen emission line filter in the PST works. See this URL instead. Normally, you'll want the tunable Fabry-Pérot etalon filter centered on the H-alpha line at 6562.8 Ångstroms. That produces the maximum contrast in solar surface detail. The PST has an adjustment ring (figure 4) for tuning the wavelength the etalon transmits. Adjusting this ring back and forth will bring out maximum detail in sunspot groups and maximum contrast in prominences along the edge of the sun.

This leads to a neat trick. With a scope like this, you are looking at such a narrow slice of the spectrum that modest velocities (by solar standards) will Doppler-shift the H-alpha line out of the bandpass of the filter! If you're looking at a sunspot group on the surface and you detune the filter to the long-wavelength side of H-alpha, you may start to see darker filaments and streamers appear against the surface of the sun. The reason they look dark is because their emissions are being Doppler shifted towards shorter wavelengths. That means this is stuff that's coming towards you! Similarly, you may see different parts of large prominences on the rim get brighter or darker relative to each other as you tune the etalon. That tells you the different parts of the prominences have different velocities towards or away from you. With a bit of practice and deduction, you can get some sense of what shape these "clouds" really are and how they're moving.

This, by the way, is one of the important tools that the big kids use for solar astronomy, which is why professionals want filters with bandpasses as narrow as 0.1 Å. Strange as it may seem, solar astronomers are always complaining about not having enough light.

So, am I getting $500 worth of fun out of this scope? Oh, you betcha!

More next time....

ADDENDUM: Dear folks, You want photographs? Okay, how about this one?

(The link is here.) I wasn't aware that this had even been an "APOD" photo* until tonight. I was Googling for some information on solar phenomena for my replies and stumbled across this. My first (and so far, only) APOD! This is a rather so-so scan of a rather brilliant print (if I do say so myself) of a rather spectacular prominence. For its time, circa 1971, it was considered a noteworthy achievement, being able to produce that much local contrast and detail enhancement without blowing out the highlights or the shadows (easy in Photoshop; not so easy in the darkroom). It ended up being on the cover of Science magazine in the early '70s. Not only my first APOD photo but my first magazine cover! (Well, nobody said how recent the photograph had to be...) If I can find my print of this photo, I'll try to make a better scan and post it. —Ctein

*Astronomy Picture of the Day

Featured Comment by David Anderson: "Perhaps just an idea to issue a warning that no-one should attempt to view the Sun through any optical instrument unless they are using suitable solar filters. Please don't try this with an ordinary telescope or binoculars, your eyesight will be permanently damaged."

Featured Comment by Animesh Ray: "Dear Ctein, Thanks for the article, but more for the photo. I actually saw the cover in early '70s and, amazingly, remember it! I was an undergraduate student then, back in Calcutta, and I chanced upon this image of solar eruption on the cover. It was just an amazing sensation to ponder the real magnitude of these eruptions. I still remember having 'pored over' this photo for hours and dreaming about it, in the USIS library on a dingy lane near College Street in Calcutta.

"Just to revisit the old times, I looked for and found the issue of Science with Ctein's photo on the cover. It is amusing to re-read Linus Pauling's acerbic letter to the editor in that same issue!"

What?...No Sunspot Images from your new scope?

;~)

I have often wondered about these scopes...

Much Appreciated Ctein!

Posted by: Jay Frew | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 09:30 PM

Ctein,

Trust you to buy this 'scope during a period of low Solar activity :-p

Enjoyed the article, and look forward to seeing some photos taken through it. C'mon, this is a photography blog, after all :-)

Posted by: Miserere | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 09:38 PM

Cool! I worked at Orion for a couple of years, back in the late '80s...

Posted by: Semilog | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 09:45 PM

Ditto what Jay and Miserere said: where are the photos?!

I was curious at your mention of seeing the floaters in your eye. The way you write this implies that they're common; I'd always thought they were pretty rare. I have a prominent one which I can always see, and have had it for 25 years or more, but I've never met anyone else who's even heard of floaters.

Posted by: Murray | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 10:01 PM

I didn't understand all of this ... but I was very happy to see it, regardless. Thanks, Ctein!

Posted by: Ben Rosengart | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 10:04 PM

Given the minimal solar activity for most of this year ( 242 days -76%- with no sunspots) I hope you got a good deal on this gizmo. You probably would get more excitement getting a $25 used spotting scope and looking at the next door teen's face.

Just fooling. Have fun. I remember how exciting it was to whip up a sun viewer when I was 9 or 10 to see the black spots.

Posted by: Ken Tanaka | Tuesday, 17 November 2009 at 10:24 PM

First of all Ctein, you are completely insane. Take that as a complement. Also, I too was bummed for the lack of sun pics.

Second of all, your description of "eyeball floaters" made me go "huh." Every once and a while I have something that I guess I would say appears to float across my field of vision, sort of like glitch in the Matrix, but I never really thought anything of it.

Blowing my mind even more, the Wikipedia page for "Floater" is specific to eyeball floaters:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floater

Posted by: Justin Watt | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 12:55 AM

Thanks, really enjoyed the post.

I always thought that solar scientists are looking at the sun with wide band instruments and taking spectrograms to study the "chemistry", and now I have learned that they use very narrow band and study the dynamics through doppler effect.

But there is a number I don' understand. You tell me that 40mm aperture is enough to enjoy the sun with 1 Angstrom bandpass. But then, for a filter with 0.1Angstrom 70mm should be enough. How can solar scientists complain about having not enough light?

R.

Posted by: Roberto C. | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 01:24 AM

How idiotic of me...

I thought we were about to discuss about Nina Simone.

Posted by: Iñaki | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 02:42 AM

Dear Murray,

No, almost all folks have floaters to some degree or another. For a very small fraction of the population, they are a serious visual problem. For a very small fraction of the population, they are essentially nonexistent. For all the rest of us, they're something that usually doesn't present any visual difficulties...except in circumstances like these.

Monochromatic, collimated-light, monocular viewing is the perfect recipe for producing clear visual images of floaters.

Sigh.

~ pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 02:58 AM

Dear Ken and Miserere,

Indeed, the sun is rather late out of the gate this sunspot cycle. Very tardy of it, if I do say so myself.

However, a "quiet sun" is never, ever truly quiet. Even during sunspot minima, there are always plages (bright patches on the surface of the sun), flares, dark filaments, and prominences. It is very rare to have a day when there's nothing interesting going on.

I would say that we've gotten in about 20 days of viewing since we bought the scope. Indeed, I have seen sunspots on fewer than a quarter of those days. But out of those 20 days, there've only been two when I didn't see anything worth looking at. On half-to-three-quarters of the days, there were one or more interesting prominences along the edge.

In fact, the day we bought the scope, there was a small but quite decent sunspot group with nice filament activity in the middle of the disc and two prominences on the edge. Over the next several days, we tracked that group as evolved and rotated out of view, and as it passed the limb of the sun, it produced a very fine prominence.

For an idea of what the Sun is doing every day, check out the Big Bear Solar Observatory (where I used to work) website:

http://www.bbso.njit.edu/cgi-bin/FDHALatest

The photograph for Nov 17, 19:00 UT matches very closely what I saw (with nowhere as good resolution, of course)this morning. I saw all three plages, the dark filament across the bigger one, and the U-shaped darker cloud closer to the limb.

~ pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 03:10 AM

Perhaps just an idea to issue a warning that no-one should attempt to view the Sun through any optical instrument unless they are using suitable solar filters. Please don't try this with an ordinary telescope or binoculars, your eyesight will be permanently damaged.

Posted by: David Anderson | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 08:05 AM

Floaters are indeed a real problem and a common problem. They are more common as one ages. They range from being a nuisance to a visual impairment. They are more noticable when looking at something bright. They can sometimes be much more prominent in one eye vs the other. Sometimes they come and go (when they are a result of thickened eye fluid). Often they are just debris floating around forever.

The important point is that chronic floaters do not lead to blindness or anything, which is good because there is really no cure or treatment.

If you have floaters that are new or significantly increased or if you see flashes of light with them - see a doctor.

Posted by: Ed Taylor | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 10:05 AM

Perhaps just an idea to issue a warning that no-one should attempt to view the Sun through any optical instrument unless they are using suitable solar filters. Please don't try this with an ordinary telescope or binoculars, your eyesight will be permanently damaged.

My most embarrassing moment with a telescope was when I couldn't locate the sun in the sky with the solar filter attached. Fortunately I didn't try the spotting scope. Still looked at the sun too long that day.

Posted by: Tom | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 10:54 AM

The important point is that chronic floaters do not lead to blindness or anything, which is good because there is really no cure or treatment.

Yet another reason I should have a clone growing in a tank right now. I'm about to the point where lathering up my brain in stem cells and lowering it into a new body would be a good idea.

Posted by: Tom | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 10:56 AM

Ah, floaters. They are the bane of my optical existence.

Floaters are generally the de-pigmented "ghosts" of red blood cells that manage to leak out of retinal capillaries into the eye. They are indeed completely harmless, but the magnified shadow they cast upon the retina makes them annoying far out of proportion to their tiny size. I had a retinal tear in my left eye over a decade ago, and this released a boatload of floaters into my field of vision, and they've been there ever since. The four or five I have in the other eye are trivial by comparison. This killed my birding hobby; I used to visit hawk-watches every spring, but now it's just too frustrating. About 90% of glimpses of distant hawks turn out to be a floater. They're not nearly so annoying when it comes to photography, at least for me, as the viewfinder of a D-SLR has a different apparent distance and a narrow enough field of view that they are rarely visible.

Posted by: Geoff Wittig | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 11:15 AM

This was a Xmas gift, huh? Makes me think of A Christmas Story: "You'll burn your eye out!"

Posted by: JonA | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 11:51 AM

About the floaters and flashes of light..

Flashes of light can be a detaching retina.

Had a friend go through this a couple weeks ago. (Omaha NB USA area.) Prompt laser surgery and all is well. But HE DID NOT KNOW until his wife INSISTED he see an ophthalmologist, that he was in trouble!

So good info from all on this blog.

Posted by: Mark Hugoson | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 12:03 PM

Curse you Ctein! I have successfully avoided buying a PST for years, and now you bring this up.

Fortunately, I have to buy a Rotatrim and some printing paper (via TOP, of course), so I have an excuse not to run down to Orion.

Posted by: farshore | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 01:38 PM

Dear Tom,

You shouldn't be embarrassed. That's why I included a tip for aligning this scope by checking the shadow on the barrel. I mean, it's not like you can look through a finder scope to center the main scope on the Sun!

Well, not more than once.

================

Dear Roberto,

People still do "chemical" studies of the sun, but at this point they're doing them to so many decimal places that collecting enough photons is STILL a problem.

But, you are correct in your understanding; narrow-band observing is how most of the work is done. There are also a bunch of other elemental emission lines that are worth looking at and provide very useful information about the sun (like the structure of the magnetic fields) that are nowhere as bright as the H-alpha.

Your math was a little off, but I get your point. You're arguing that if a 40 mm aperture provides enough light to enjoy 1 Å, then 10 times the aperture (130 mm diameter) should be good down to 0.1 Å. It's not quite that easy. First, the filters aren't 100% efficient. I don't have the curves at hand that I need, but I'm going to make a wild ass guess and say that you'd actually need a 200-250 mm aperture to get the same viewing brightness at 0.1 Å.

(One can get supplemental filters for the PST that will take it down to 0.7 or even 0.5 Å. That substantially improves viewing contrast. The filters costs as much as or more than the PST. The image will get enough dimmer that I'm not sure I will ever invest in one of these. If you're really interested in higher contrast viewing, you'd probably want to go to the next larger scope, which is MUCH more expensive - circa $3000.)

But, we're not done. That 250 mm aperture gives you the same viewing brightness only at the same magnifications. And the useful magnifications for a 40 mm scope are pretty limited; it is diffraction-limited to three arc seconds resolution (with some clever image-processing tricks, you could probably improve that by a factor of two). But a 250 mm aperture can resolve down to half an arc second, and good seeing will support that. To take real advantage of improved resolution, you'd want to increase the magnification by a factor of four or five. Which means, to keep viewing brightness up, you need to double the diameter again. A 20 inch solar telescope is a SERIOUS research instrument: The one on the roof of the astronomy building at Caltech was, I think, an 8 inch scope and was used for doing serious research. The brand-new, totally-state-of-the-art NST scope at BBSO is 64 inches.

It gets worse. The big limitation on seeing for solar astronomy is atmospheric turbulence! Heat ripples! The scope at Caltech was a good research tool because it pointed across the parking lots and athletic fields-- acres of uniform land that created a nice rising column of stable air. BBSO was built on a little artificial island in the middle of the lake so that it would be surrounded by uniform-temperature water. It gets fabulous seeing. For a long time it was the consistently best solar seeing in the world. For all I know it may still be.

Even so heat ripples are a real problem, so you want to keep your exposure times as short as possible to freeze the turbulence; that's the only way to get sub-arc-second resolution. The smaller the fraction of a second, the better.

That's why solar astronomers always whine about not having enough light.

In fact it was just this problem that led me to invent the CCD array in 1971... unfortunately, two years behind Bell Labs, so no fame and fortune for me! Taught me the importance of doing a literature search BEFORE putting in lots of brain power.

~ pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 02:59 PM

Hey Ctein,

Glad you found the APOD. It was what got me back into photography over three years ago. A programmer friend of mine recommended it.

Cheers,

Chris

Posted by: Christopher Lane | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 05:17 PM

Dear Animesh,

That's pretty cool! It's a pleasure to find out my print was so inspirational.

I found an original print and scanned it. It's posted here, as a high-quality JPEG:

http://ctein.com/TOP/Ctein-BBSO--3-31-1971001.jpg

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 09:34 PM

Thanks Ctein!

Another example of why I love this site. The joy of looking at the "forbidden place" in the sky! Back in the '80s I used to work at a photo store that sold Celestron scopes, and picked up an 8" SC kit on an employee discount from the factory. Since I was the in house "expert" I could try out all the goodies so I could talk to customers about them. When Mars was in opposition in 1986 some friends and I hauled that scope up to 4500 feet in the South Cascades to observe it. The next morning I brought out one of the goodies I could borrow, a full aperture solar filter, It was amazing to look at the Sun that way, to see that it was not a bright featureless ball, but had texture and variation. It truly is something to look at that "forbidden place", let alone under magnification for as long as you please! If you ever get a chance to observe the Sun with tools like this take it!

Posted by: Sean Murphy | Wednesday, 18 November 2009 at 10:30 PM

Thanks again Ctain

and apologies for the wrong math, I forgot to go back from radius to diameter, shame on me!

In any case, I'm not at all surprised that the more light you have, even from the sun, the better it is. Just it did not come out straight from the firts post, and now you have give us plenty of reasons (and a nice connection to digital photo via the CCD sensors invention)

Posted by: Roberto C. | Thursday, 19 November 2009 at 03:18 AM

Ctein,

It's great to know that amateur solar astronomy can be affordable. I have in the past looked at the work of Thierry Legault - http://astrosurf.com/legault/ whom I am certain does not use anything affordable, but his results are spectacular.

Cheers,

Michel

Posted by: Michel | Thursday, 19 November 2009 at 03:29 PM

Dear Michel,

Yes, Thierry's site is great.Includes lots of excellent technical information, too.

Good H-alpha filters are expensive.Often more than the scope. But you can do great white light solar photography, as Thierry demonstrates, and the equipment for that can run you under $1,000. His remarkable ISS-against-the-Sun photo is a masterpiece of planning and technique, not equipment.

Thierry's current preferred scope for night astronomical work costs $3,000.

Yes, by the time you get done with all the important ancillaries (a good mount can cost more than a scope), your bills can mount up... the same way the purchaser of a $2K-$3K DSLR body can easily spend more than that on lenses and accessories.

But, you can do award-winning astrophotography for a total expenditure of under $3,000. Probably under $2K, if you really know what to buy. And that's NEW gear-- there's a good market in used gear at prices from 30% to 70% of new.

Great astrophotography requires lots of time, skill, and knowledge. It does not require deep pockets.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Friday, 20 November 2009 at 01:40 PM