By Ctein

Some of the feedback I got to my last column led me to realize that a lot of readers don't know what constitutes a good proof sheet. To put it succinctly: A good proof sheet doesn't make your photographs look good; it shows you what's in your photographs, conveying as much information as possible about the content of your negative or digital file.

Now that we're into the digital age, not everybody uses proof sheets. Many photographers prefer to work with their photographs entirely on-screen. For a variety of reasons, I still find proof sheets extremely valuable. Every photographer's preference is entirely personal and idiosyncratic. If your choice is to work on-screen, that's fine with me—I'm not going to belabor my choice or debate the two approaches. If you're curious to know the way I do it, however, this column might interest you.

Proof sheet photographs are a lot like RAW digital files. They tend to be flat, dull, and lower than you would like in contrast and saturation. Show an untrained viewer your proof sheets and they will be unimpressed with your photography. There will always be a few exceptions; occasionally a photograph will be so striking that it stands out no matter how it's reproduced. I have a few of those in my portfolio. But by and large the vast majority of your portfolio-quality work won't fall into that category. A photograph that looks striking in a proof sheet will likely prove to be a winner—but most of your winners won't look striking in proof sheets.

Darkroom proof sheets are usually, but not always, contact prints from the original film. Hence they are often referred to as "contact sheets." I prefer to say "proof sheets" because this isn't always the case. For example, a lot of workers, myself included, learned the trick of putting three strips of 35mm film in a 4x5 film carrier and enlarging by a factor of two to print nine 35mm frames on a single 8x10 sheet of paper. It makes studying the details and visualizing the final crop a lot easier. Also, the tonal placement is closer to what you'll expect to see in a final (enlarged) print.

For normally-exposed negatives, the usual procedure to making a proof sheet is to choose a paper grade substantially lower than the one you would normally print those negatives on. In color work, that simply means finding the lowest contrast paper you can that's on the market; there aren't a lot of choices. In black and white work, it means dropping at least a full paper grade below whatever is normal for you. The exposure should render middle grades approximately correctly, but blacks should not look solid black; there should be a clearly visible difference in print density between the unexposed edges of the filmstrips and the entirely clear area between strips. If your negatives are unusually dense, you won't be able to maintain that difference and there will probably be some blocking up in the shadows, but it still will be a lot less than you would get in a normal-contrast print.

Here's a tip that will speed up your printing if you're making contact proof sheets. Set up your enlarger as if you were making a typical enlarged print from one of your negatives, say an 8 x 10 from 35mm film. Set the lens aperture to some plausible value for your printing. The exposure time you end up using for a decent contact sheet, combined with the way the individual frames look on the sheet, will give you a pretty good idea of what your starting exposure settings should be for making enlargements. Write the proof sheet exposure information on the margins or back of the sheet for later reference.

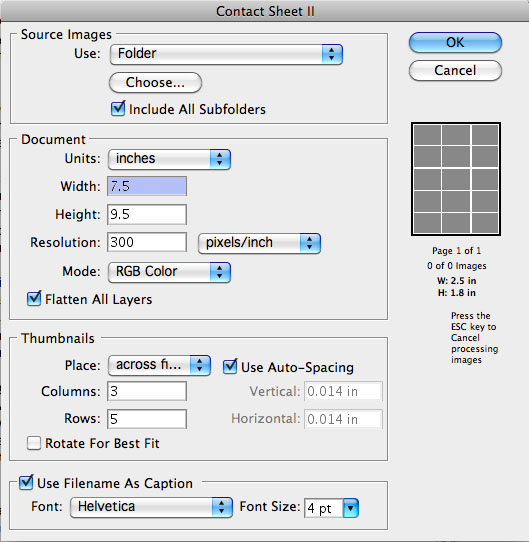

Fig. 1

If you're proofing digital files, enlargement is entirely virtual. I settled on 15 frames/sheet. It puts the same number of photographs on a proof sheet that I got from contact printing my 645 negatives, which is big enough for me to see what's really in the photograph. I still use the Contact Sheet II automation in Photoshop, because it's what I know and it works for me. Figure 1 shows my control panel settings. (Most image processing software will give you some way to generate a proof sheet, but I don't use these other ways, so please don't pepper me with questions about how to set them up correctly.)

You'll notice in the control panel that I set the effective size smaller than a full page. I did that so that it left room on an 8.5 by 11 sheet for me to punch the edge of the page for a three ring binder and room at the top for me to add title and date information about the "roll." I have a simple little action in Photoshop that takes the proof sheet, expands the margins accordingly, and lets me type information into a text layer at the top of the page.

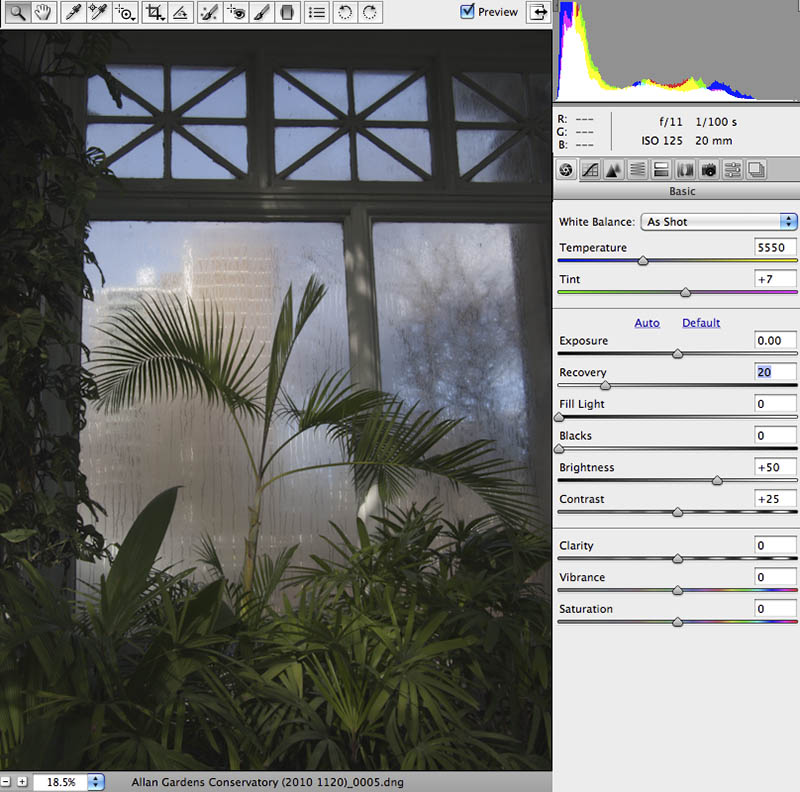

Since I work 99% in RAW format, all my photographs get massaged by Adobe Camera Raw (ACR) before Photoshop merges them into the proof sheet. The default settings for ACR are not ideal for reviewing photographs. They produce a pleasing image, but it's too contrasty and it doesn't show the full range of information in the RAW file. Kind of like the difference between looking at a camera JPEG and a camera RAW file, although not that extreme: The JPEG looks attractive, but the RAW file shows you what's there. Figure 2 shows the settings I saved as my default settings in ACR. The two important differences are that I've added 20 points of highlight restoration, which is enough to avoid excessive clipping in the highlights without significantly compressing the midtones, and I've moved the black level slider all the way down to zero. Also check the Tone Curve Point tab in ACR to make sure that the "Linear" curve is selected.

Fig. 2

That's pretty much it. Not rocket science. Not even really bottle-rocket science.

Making decent proof sheets doesn't have to be a burden. I'm happy to say that although I am years, even decades, behind making enlarged prints of all of my very best photographs, my proof sheet files are 100% up to date.

Ctein

Ctein's regular weekly column, which was delayed for one day this week, will appear once more on Thursday (next week), and then will be switching to a new time slot—Wednesdays on TOP.

With your particular methodology why would you leave brightness at +50 and contrast at +25? I have zeroed out these items in my camera raw defaults to better identify files with the best capture quality and to eliminate false indications by added brightness and contrast.

Posted by: james wilson | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 11:05 AM

Dear James,

'Cause with the three digital cameras I've used so far, zeroing those settings out produced a result that looked substantially darker and dingier than the photograph should and also didn't look visually consistent with the histogram information.

If it were just one camera, I'd attribute it a systematic exposure error in making the photos. Not with three.

So why does +50/+25 work better and more realistic? Idunno. Decided I didn't really care enough to investigate. But if someone here has the straight dope, I'd not mind being educated.

A null value is not inherently better in any of the ACR settings, vis "Recovery." But, use whatever works best for you.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 12:02 PM

I did my proof sheets completely differently. All you had to do was find the exposure point where the film base effectively disappeared from the picture, giving you the darkest black you will be able to achieve (I even had a list of film base anti-fogging levels and would adjust the f-stop on the enlarger lens to adjust the exposure: time was constant (and, if I remember correctly, 30s for my favorite paper, Agfa Brovira). Development was also held constant. That gave me the best feel for the ability of the negative to be scaled up to a full-size print. Obviously for B&W only: I am slightly color blind, something that I discovered only after going through several boxes of Cibachrome and wondering why everyone was saying my color balance was off when I couldn't see it...

Exploring the right adjustment to get the blackest black that still retains detail is an ongoing digital project.

Posted by: John F. Opie | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 12:36 PM

“Ctein's regular weekly column, which was delayed for one day this week, will appear once more on Thursday (next week), and then will be switching to a new time slot—Wednesdays on TOP.”

What? Are you trying to increase your audience share for sweeps week? As long as you don’t trot out sensational stories about the dreaded Chupacabra, demon of the border land, I can live with that.

I do enjoy the articles by Ctein regardless of the day they appear.

Happy holidays

Posted by: Ken White | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 01:04 PM

As I understand it, a value of 50 and 25 for Brightness and Contrast respectively, ARE the calibrated "zero" / "normal" values (so far as there is such a thing), going into a Raw conversion. We start out by assigning a "boring middle" value, from scratch. Using the lowest possible value, zero, would be an extreme choice (not a neutral one); because these settings are absolute.

When applying ACR adjustments to a JPG or TIFF, however, the "zero" point on these sliders now DOES logically mean "no change". It's a quite different context: one where adjustments accumulate, and settings are relative.

Posted by: richardplondon | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 01:33 PM

Dear John,

Doesn't sound "completely different" to me, just slightly different.

As I said to James, whatever works for you-- there's no one right path (if there were, I'd have titled this "The Only Good Way to Make a Proof Sheet").

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 01:40 PM

I use photo mechanic for contacts, print a wack of them at a time automatically, titles and photographers info on the sheets. Can't live without it.

Posted by: glennbrown | Friday, 26 November 2010 at 01:45 PM

This is the best writing I have ever read on making proof sheets. It was only after doing photography for 25 years or so that I finally put 2 and 2 together and realized I needed to be making my proof sheets softer instead of making them look good. That information, plus the tip on how to use the proof sheet to estimate the starting time for printing 8x10s - great stuff to know!

Posted by: Jeff Damron | Saturday, 27 November 2010 at 09:13 AM

The Photoshop contact sheet utility is great.

A couple years ago I used it to print 6954 images ganged together into an 8 x 124 foot print

24x96 sections actually, it's not so hard to find an 8foot wide printer but hanging a 8x30 foot print can be a drag. That's about a fifth of it in the picture.

Posted by: hugh crawford | Sunday, 28 November 2010 at 12:35 AM

Dear Hugh,

ohmigawd.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Sunday, 28 November 2010 at 04:22 AM

I think your description of a darkroom b&w proof sheet requiring a lower grade of paper presumes one uses a condensor light source for enlargements. For those of us who (properly!) used cold light or other diffuse source, such is not the case, at least in my experience.

And, especially for sheet film, my standard for proofs was that they be "better" than 90% of others' finished prints. With correct exposure and development, this could be achieved, leaving me with minimal manipulation during enlarging.

I realize this perspective raises a lot of old "discussions", but after nearly 40 years of photography, I know I'm right. :D

Posted by: WeeDram | Sunday, 28 November 2010 at 09:14 AM

Dear Wee,

Nope-- I was never a fan of condensor enlargers. Always used diffuse light for my printing.

While diffuse light requires an overall higher paper contrast with silver B&W films to match the overall contrast of a condensor print, the principle is the same. I want my proof sheets to show me as much of what's in the negative as possible (without excessive tonal distortion, of course). That means no d-max in the proof sheet wherever there's film.

Best way to get that without blowing out the highlights or excessively lightening the midtones? A grade less paper contrast.

If you want your proof sheets to be works of art, be my guest. As I said to James and John, whatever you like. But it's got nothing to do with the enlarger light source.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Sunday, 28 November 2010 at 02:38 PM

Ctein: Thanks for the explanation, which makes sense.

In the case of LF (4x5 in my case; I physically can't handle anything larger), I can pretty easily inspect the negative by eye. So I would tend to follow your formula for 35mm.

My reason for making a "fine" proof print is to have a quick check on exposure/dmax to my standard paper grade. If I owned a densitometer, I might do otherwise.

Well, I do love a fine proof. :D

Posted by: WeeDram | Thursday, 02 December 2010 at 02:43 PM