By Ctein

Over the past several weeks, many readers have raised concerns about the permanence of photographs, whether film or digital. Truly, they have every reason to be concerned. It's a problem that has bothered me ever since Henry Wilhelm opened my eyes to this in the mid-1970s (we have been lifelong friends, since).

In practice, photography has not proven to be a very durable set of media. The examples people trot forth of photographs that have survived a century are almost never in their original condition; they are merely recognizable images. Worse, that enduring photographic record of the 20th century, while a far more extensive documenting of humanity than has ever existed before, is but a small fraction of all the photographs made and now lost.

We have the mistaken impression that photography is durable because what has endured is so extensive and we remember victories, not losses. Almost axiomatically, there is little way to remember the losses. It's a kind of cultural posttraumatic amnesia; the photographs that disappear from view mostly get forgotten.

This, of course, is what concerns us all. Photographs are our memories! Unfortunately, we are badly brain-damaged, and while we may be dimly aware of it there is very little we can do about it.

Oh sure, almost all those old photographs (if they physically exist, and most of them don't) can be restored. That is, in part, my business. It's expensive. For what I charge to restore a mere dozen or so individual photographs, you could have all the data recovered from the most decrepit and ancient hard drive. That's an important point: theory says you can preserve old photographs against deterioration and restore them when they do deteriorate. Theory also says you can recover digital data from almost any medium at any time. All it requires is a sufficient application of expertise and money. Especially money.

Nice theory. In practice, how often does that happen? Very rarely. The theoretical permanence of well-processed black-and-white photographs and prints or of well-processed Kodachrome film is as irrelevant to the collective discussion as assuming that everyone will follow proper archiving practices, backups, and storage-medium/format updates for their digital photographs. Those media don't constitute the vast majority of photographs and most of the photographs made in those theoretically-durable media were not well-stored and preserved. If your stuff still looks good, I am happy for you; just realize that you are one of the lucky few.

In the real world, no modern photographic medium, analog or digital, has shown itself to be durable. It only lasts when ordinary people take measures that are, well, extraordinary.

I have been pondering whether the situation is now better or worse than it used to be, and I don't have a clear-cut answer. Mostly that is from a lack of historical perspective; we are simply too newly into the digital age to know what the future will bring.

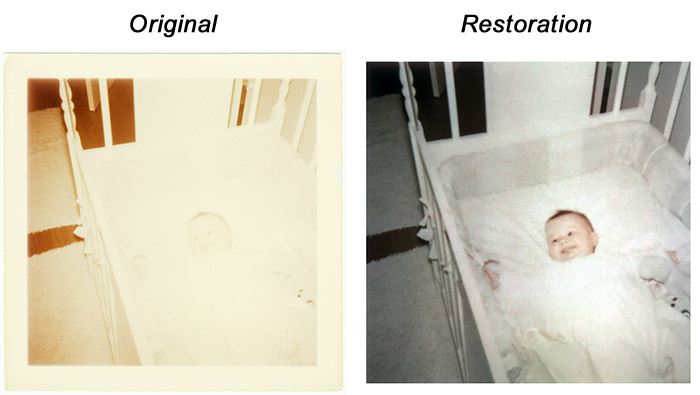

1. On the left, an all-too-typical color photograph from 1950. It's essentially blank to the naked eye. As the right figure shows, it's possible to recover the image to a satisfactory degree, but hundreds of dollars of work went into achieving this. What percentage of old photos will ever get this treatment?

In the case of film photography, the record is all too clear. Most photographs, slides, negatives, and prints, from 1946 through 1960 are already deteriorated to the point where they are essentially unviewable (illustration 1). Most of them are recoverable but never will be recovered. Not enough money, not enough time, not enough skilled restorers on the planet.

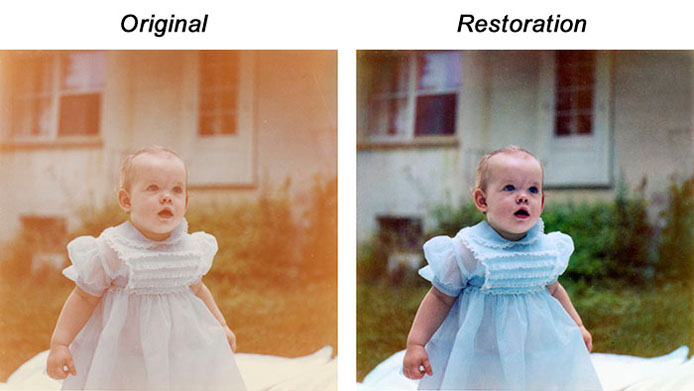

2. By the early-mid '60s, prints were a lot more durable than in the '50s, but that's damning with faint praise. This degree of restoration only costs in the double-digits, but that's still more than most photos will ever receive.

The photographs from 1960 to about 1980 are on the same path (illustration 2). On average they are in better shape because materials improved and less time has passed. On average they are in worse shape because of the increasing shift to chromogenic materials which, back then, lacked in permanance (although God knows they were much better than their 1950s predecessors). Give it another 20 years and most of that cultural record will be gone. I'm not talking about the really important events that were documented up one side and down the other; I'm talking about the mass cultural record that those of us alive at the time made for our own pleasure and to preserve our own memories.

A third of a century of photography is already mostly lost. Very little of it will survive intact another 25 years.

Things got a lot better starting in the early 1980s. E6, C41, late EP2, and RA4 film and paper processes all led to increasingly permanent materials. By the end of the Film Era, chromogenic prints had better display permanence than even dye transfer as well as an entirely acceptable dark-keeping lifetime. Late-generation E6 slides are, in practice, as permanent or more so than K12 Kodachromes were. These photographs will continue to deteriorate, but nowhere as rapidly.

Even black-and-white, on average, has become more permanent, primarily because the vast majority of earlier stuff was really badly processed. I get to see the evidence for that regularly; it is not a pretty sight. Black-and-white RC papers, for example, may not be as durable as fiber-based papers when given ideal processing, but I assure you that a far smaller fraction of fiber-based prints ever received anything close to ideal processing. That theory-vs.-practice thing again.

That is an extremely abbreviated history of analog photographic permanance. So abbreviated, in fact, that it includes numerous minor inaccuracies. The overall picture, though, reads truly enough; view it in broad strokes.

So what about digital photography? The initial period is going to be rocky. Hell, it already has been rocky. I'm going to guess that the majority of photographs from the first decade of the Digital Era will be lost (for some definition of "first decade:" your dating system may differ from mine). Again, I'm talking real practice, not theory. With digital, it's even more about practices than inherent characteristics of the media. Said practices were very, very sloppy.

I suspect that is changing rapidly. Your average camera-wielders are getting much better about preserving their photographs, much more quickly than I expected. The reason, I think, is because the everyday records and data of one's life are going increasingly electronic.

My housemate, Paula, and I were surprised this last year when the IRS told us they would no longer be sending us paper tax forms to fill out; we would have to download them from online. Hardly a burden; we still file on paper, so that's what we did. What really startled us was to learn how much of a minority we are in; only about 5% of all tax returns are filed on paper these days. We had no idea.

That's the way the average citizen's world is very rapidly moving, and in that world there are strong forces at work to improve overall digital durability in practice as well as theory. In the dark, on the hard drive, all bits look the same. Doesn't matter if it's someone's photographs, their music, video, or movie collection, their electronic books, their bank statements and check stubs, or their tax returns. As a pleasant, inevitable side effect one's personal photographs will get preserved and maintained along with all the rest of one's electronic life.

Analog photography lost more than a third of the century. I'll be very surprised if digital photography loses even a quarter. Maybe not even much more than another few years beyond the already-past decade.

I hate it when any photographs are lost. But I've come to sincerely believe that we are better off now than we used to be in the Analog Era. I've seen how badly that worked out.

Ctein

Ctein, the author of Digital Restoration from Start to Finish, writes a regular weekly column (not always on restoration issues—sometimes, it's parrots) for The Online Photographer that is published on Wednesdays.

Featured Comment by Jim: "It always comes down to money! But, why should we preserve them? I read recently that there are 43 billion photos now uploaded to Facebook, another five billion to flickr. And, I would guess, perhaps trillions living on hard drives around the world. I'm not convinced it's a good thing they survive.

"I burned tens of thousands of negatives and prints from 50 years of my photography (I'm a photojournalist) heavily documenting my area a few years ago because I couldn't give them away to historical societies, etc. Sent out dozens of letters, made numerous phone calls. Too expensive and space-intensive to store and conserve them, they all said. Too expensive to scan and convert them all to digital, they all said.

"For most of my photography career I worried about archiving prints and negatives, and then digital files. But I don't concern myself with it anymore. Most of these trillions of images being constantly recorded these days will never be looked at again anyway.

"Perhaps they should be as impermanent as our own memories, which gracefully degrade as we age and then disappear when we die."

Mike replies: That's a painful story, Jim. I almost hate to say this, but it's at least possible that you destroyed your work during its stay in the "Trough of No Value." That doesn't mean it might not have been valuable to future generations or historians, just that it wasn't valuable to them yet.

Dear Mike,

I've mined out parrots, for the nonce, but I am very seriously contemplating several columns on tea.

Really.

pax / caffeinated Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 05:23 PM

Because this is the turn of the millennium, and because a thousand years no longer seems that long to me (books of the Bible were written some 2500-2700 years ago; the United States has been around almost a quarter of that time) I once thought that it would be interesting to provide a grant to the Minnesota state historical society to do a photo documentation of Minnesota life now, with the hope of passing that down 1,000 years until the turn of the third millennium. I think the governmental situation is stable enough now that there would be a good chance of doing that (of finding institutions that would actually preserve the record.) But that brought me immediately to the question of durability of photography. I thought perhaps that you could make, say, 1,000 photos of Minnesota life, with some kind of captioning, preserved on a range of hard drives, or thumb drives, and leave enough of an annuity (perhaps protected from other uses by a state law) that these could be updated every ten years or so. But, I thought, mostly likely somebody along the line would screw it up. What you really want preserved are the physical photographs themselves.

So then I thought -- and I don't know if this would work, perhaps you (Ctein) can tell me if it would -- how about three-color aluminum plates from an ordinary high-quality printer? Instead of saving the printed piece, you'd save the plates, which would remain printable as long as anybody remembered the three-color process, which, short of Armageddon, should essentially be forever. Isn't aluminum pretty stable? If you sealed ultra-clean plates inside of some ultra-tight, chemically stable and neutral box (acrylic, or some such) shouldn't they last essentially forever?

JC

Posted by: John Camp | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 05:39 PM

Thank you Ctein for this great reminder from an expert (I prefer the french wording: "l'homme de l'art" !).

This is exactly what made me step into the digital world. I still have some 1918 Lumière color print from my grandfather (well I can see they used to be in color), just as glass plates from my other grandmother (alas, storage in the small cardboard boxes after two world wars and exotic places had the gelatin divorcing from the glass support), a pretty collection of 3000 slides from my father (Kodachrome) that I try to salvage one at the time...

I won't even mention my own films, either B&W, hastily processed with various chemicals or the C41 from the next door shop and will hide with shame from experiments with slides of various origins !

I have the deposit of the family hoard, starting circa 1870 (looks like) up to now, among all those pictures (negatives or positives) following several generations of worldwide tribulations... Yet so few of them are "usable", meaning that are worth the time (or the price) to restore them to an almost proper state ! Some portraits, some exotic views, around one hundred maybe on a stock of several thousands!

I'm now a firm believer in digital "immortality"...!

Jacques

Posted by: Jacques Pochoy | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 05:45 PM

"I hate it when any photographs are lost. But I've come to sincerely believe that we are better off now than we used to be in the Analog Era. I've seen how badly that worked out."

100% agree. And it will get easier.

Posted by: Steve Jacob | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 06:53 PM

I agree with everything you say, but don't think the younger generation coming through are going to be any better. I've four boys between 19 and 27 at home, none of whom are keen photographers but they all have thousands of photos on their computers. Those with laptops never back anything up, and every three or four years the laptops die, losing everything. After years of nagging I convinced the only lad with a desktop computer to use a backup external hard drive since he had more photos of the family than anyone else.

Well yesterday his hard drive died, and six hours later the external drive died.

You can only try.

Posted by: mark lacey | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 07:10 PM

Permanence of the photographic medium, whether digital or film, is only one part of the equation. The other is human; a lot of valuable documentary images are simply thrown out when clearing out Grandpa's house if other family members have no interest in the subject, or don't even bother to look. And since we are talking about retaining a record the image needs supporting information to actually retain its historical value. Is anyone still alive to identify that infant in the crib!

Posted by: John Sutherland | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 08:01 PM

Great post. Very informative.

As a professional photo archivist this mirrors my experience over the years precisely.

Posted by: Timothy E J Atherton | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 09:10 PM

Though I'm making efforts to save my family's photographic history, both still and moving picture, I realize that nothing is forever. All I can do is preserve as best I can, with the technology available, for the next generation and hope they can do the same.

Posted by: SteveO | Wednesday, 15 June 2011 at 09:46 PM

I am glad I took film photos of my kids in the 90s as well as digital ones in the later part of that decade.

The scans I make now of that Ekta, Fuji and Kodachrome film are absolutely glorious.

While the incredibly bad and microscopic 640X480 max compression jpgs produced with that 2MPixel digital camera make me cringe everytime I look at them.

Of course, back then when I didn't have a good scanner and my 13" monitor was 256 colours with 640X480 resolution, the jpgs looked "gorgeous" and "the way to go".

Does anyone know where I can get one of those monitors now? Because on my current 1920X1280 huge 27" monitor, they look absolutely obnoxious...

It's all about perspective, isn't it?

:)

Posted by: Noons | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 02:15 AM

Ah, I wonder what digital may bring. I lost some of my early digital picture just through lack of care. Reformated a harddrive without thinking.....gone. First attempts from my Nikon scanner suffered the same faith, but I still have the films. So I could scan again if needed. Nowadays, I fussy about my data. Use the same routines every month, every week and every day. Store the orginal files from the camera, store the edited files,the make an external backup and only then format the SD card. Always 2 or 3 copies of any given file hanging around and at least on of them under easy reach.

And as for analog. Yes, Ctein you can restore pictures at a cost. But as you know every reconstruction is a bit of a destruction as well. Since most pictures suffer bigtime as time goes by. I have seen pictures faded by light, being eaten by mold, having their silver degraded, turned bright red by chemical decomposition, and yes also suffered physical abuse by man (scissors) and animal (yeps, I've even seen one or two partially eaten by dogs). An that was whilest restoring the pictures of my niece (your great book at hand) as a nice pastime. So you have to do some guesswork, you will loose some image detail (for instance due to textured papers) and you will loose some depth. But having said that I don't know what will be more durable, shots on paper in a shoebox or shots on Harddrive in an old computer on the attic. I guess a computer stands a better chance of being tossed out then a shoebox full of pictures.

O yeah, some of the pictures to be restored were printed on an early Inkjet printer with a fixed raster. Now that was nice to scan and restore.

Greetings, Ed

Posted by: Ed | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 02:18 AM

As someone who has been following this discussion with some fascination over recent months (I recently found a load of old family photos of my own to pore over: http://bit.ly/lqJWdB) I find it a rather strange irony that the one think that photos are for (looking at, generally) is the very thing that does them harm. I have a load of large prints of Rome on my walls that I had done about 10 years ago - essentially sunlight has destroyed them, and that's with 'modern' processes. I'm pleased to hear you have greater confidence about the digital media though, I've been shifting my documents along with me each time I got a new PC or whatever for the past 20 years - it's a good job storage has become so much cheaper at time went on! There's an irony there too though I guess - most digital photos are stored 'safety' on drives and dont exist as a viewable media unless you do something with them...a bit like old prints shoved in a family album somewhere, preverved from the light!

Posted by: Shotslot | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 03:27 AM

The vast majority of photographs become unimportant within say three generations?

When my grandmother died we sorted through all her slides, prints, etc. Despite many family members being present, many of the photos were unidentifiable and/or of no visual interest. No one cared. And why should they.

I think photographers get hung up on archival quality and longevity.

"Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair."

Posted by: Paddy C | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 07:58 AM

As there are so many dedicated hobbyists out there who love to play with Photoshop, perhaps a website dedicated to photo preservation and restoration is needed. People could post their photos in need of repair and others would repair them as the mood struck. There are services that do this professionally (and some voluntarily) but they tend to skew towards disaster recovery. A crowd sourced place for people to post photos they want repaired matching with people who just like to do it.

No one would make a fortune, but a few more photos might be saved.

Posted by: Dave | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 08:03 AM

As always, I find Ctein's article well thought out and interesting. As always, I find myself in agreement. But what I really want to say is how impressed I am by the restoration he has displayed here. The workmanship is incredible!

Posted by: Christian | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 08:24 AM

"We have the mistaken impression that photography is durable because what has endured is so extensive and we remember victories, not losses."

I used to drive a 1962 Ford Galaxy 500 in 1990 NYC traffic. People would ask me "are these old cars safe?" and I'd say "Of course, how do you think this got to be an old car?" (grandma stuck it in a barn for 25 years)

Of course the Ford was only slightly more unsafe than a bicycle, but they believed me.

Posted by: hugh crawford | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 08:44 AM

Not to be macabre, but a lot of the recent talk about archiving and preservation seems to forget a larger point. For the most part, our media and the rest of our stuff will out live ourselves. These mementos are precious to us but not necessarily to the people who come after us. The real danger is that future generations will just forget us or be all consumed by the effort of preserving their own memories. It is hard to be emotional about a family photo of someone you don't even recognize.

The fact that most of our memories are lost in the sands of time seems to be part of the basic nature of life. So what do I propose? Do your best to follow best archiving practices. Stop worrying. Learn to enjoy the ride and take a lot of pictures while you are at it. Our memories and photos are mostly for ourselves.

Posted by: James Leynse | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 09:10 AM

Great post, Ctein. Many times the thought of losing my photos lingers in the back of my mind, leading me to many digital backups, but that is just of my own photos from the past few years. Even my film from 10 years back was poorly handled and seems to have taken some losses, some of which I really regret.

Now I find myself with two huge totes of photo albums and scrapbooks from my grandparents, some close to 100 years old, and the daunting task of trying to preserve these for my kids and maybe even theirs. It can be a bit overwhelming.

I am armed with your latest book though, and just need to get past the fear stage and into the work stage.

Thanks for these great posts that get us thinking.

Posted by: Keith I | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 09:14 AM

"Late-generation E6 slides are, in practice, as permanent or more so than K12 Kodachromes were. "

I like to shoot a little E6 every now and then, just to mix it up a bit. Good to know the slides should still be decent decades from now---the Kodachromes our family shot in the '70s are the only ones now viewable, and they look if not "new" (how would I know?) I'd say very, very good.

And while I'm comfortably in the digital domain for both photography and say, music storage and playback, I remain more concerned about preservation there. It's very easy to change just one piece of that puzzle and workflows and even previously-automated backup schemes fall off track.

At least the "box of photos and slides in the corner" don't move on their own, and the corner isn't additionally used as a location to read mail, play games, listen to music, write documents and so on.

Professionals may use dedicated equipment to minimize exposure to harm but amateurs don't, unless it's additionally their hobby or passion.

Posted by: David | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 09:21 AM

"By the end of the Film Era..."

Don't push it.

Posted by: Will Whitaker | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 10:16 AM

In my experience, the obsession about archivability is, mostly, moot. Once we pass away, whatever we valued and kept safe will end up in the landfill, fleamarkets and thrift stores. Forgive my pessimism, but that is what happens as soon as someone enters the house with the goal of cleaning it up: take out the clutter and dispose of it.

Stuff gets lost and is destroyed not because it was not stored properly, but because, at some moment, nobody was around anymore that was interested in it.

Events like divorces, movings and so on also are moments where people just decide to get rid of that stuff they haven't looked at for years and jut to busy right now to open the boxes, find a ton of negatives and photos, and - bah, get rid of that old stuff.

Preserving your photos for posterity is not a technical challenge. You will have to make somebody interested enough in your work, so he is willing to shoulder the burden when you're no longer able to.

To give a practical tip: instead of herding everything stuffed in boxes, organize your work in a way that, should you pass away, the fellow that enters your house after driving 10 hours and then has to move on again does not have to sift through 15 moving boxes to find the familiy pictures that he wants to preserve.

Posted by: Jerome | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 10:24 AM

I've seen more than one friend lose their entire photo library because it was not backed up. It can happen when a hard drive is dropped or a laptop gets stolen. It's not usually a problem for self-identified photographers, but lots of normal folks simply don't backup their photos.

So I'm not sure we're that much better off today than in the past. A faded photo is better than no photo, after all.

Posted by: Ben Syverson | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 10:37 AM

As I said in an earlier comment, this really is one area where digital has it all over analog. The nature of information storage inherently makes it better; the effortless ability to make exact copies means redundancy is infinitely easier. With analog, even the best slide/negative duplication techniques meant some level of quality loss between generations, so even if you wanted to preserve an image by diligently transferring it to new media periodically - before it deteriorated too badly, there would still be a limit to how many times that worked before the copying process itself degraded the image beyond usefulness; and most of us didn't have the means to do more than good dupes on any volume of analog media. For most folks, their analog images are effectively dead men walking unless they're digitized. Ephemera indeed.

Posted by: Ray | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 10:57 AM

Mike, this is a good, informative article. My transparencies have had the best permanence of any of my old analog images. I have always stored them in archival sleeves in a three-ring binder, in plastic boxes.

Is there anything else that I might do to help preserve these transparencies?

Which brings to mind my own esoteric question: Why am I preserving them in the first place? I assume they will be into the great garbage bin in the sky once I conk out and eventually degrade into the same garbage bin.

Laurence

Posted by: Laurence Smith | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 11:26 AM

Sorry Ctein. I mentioned "Mike" in my post above instead of you. I guess you guys are sort of interchangeable to me, just like lenses. Attempt at humor, so humor me.

Posted by: Laurence Smith | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 11:53 AM

Time it was, and what a time it was, it was

A time of innocence, a time of confidences

Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph

Preserve your memories; they're all that's left you

-Paul Simon

Posted by: Stan B. | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 01:12 PM

I wonder at the lack of comments on a topic such a poignant implications. Maybe Mike is just letting them pile up while he attends to more interesting tasks.

Lucky me: when I was a kid, my dad processed all of his film and had printing done at Modernage, a pro lab in NYC. He used Tri-X in an East German Praktica and Modernage did all the processing. I have been scanning some of those negatives and prints for an "ancestors" Blurb book project for my kids. The quality of the media are pretty high. I am oblivious to whatever degradation has set in since the 1960s.

Very little color though. There were some K64 slides though, from the mid-1960's which have held up pretty well.

My own negatives and prints from the 1980's also appear to be holding up fine.

I'm sure that this is the exception that proves the rule though. I find faded photos mildly depressing, like they are trying valiantly but just can't maintain their integrity.

Posted by: Benjamin Marks | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 01:55 PM

I shot nothing but slides for the first decade or so of my photo obsession, and some of them (in my humble opinion) are quite good. But they're already getting difficult to access. I've been through three generations of dedicated film scanners, and the last (a Minolta 5400 dpi film scanner) is already unusable without resorting to Vuescan due to the absence of updated drivers compatible with modern operating systems.

Scanning slides means devoting a substantial block of time to finding the slide I want (thankfully they're reasonably well-organized and labeled). Then I'm slogging through the awkward software interface, spending up to an hour fussing with the actual scan until it's usable, then finally some Photoshop time. So they're accessible to me, kind of, but there's a serious bar to jump to get there from here. Needless to say, once I have a keeper in digital form, it gets backed up thoroughly so I don't have to do it again.

Compare that to digital capture- a few moments with Adobe camera raw, whatever Photoshop work the image requires, and it's ready to go. And the digital negative (raw file) is still there any time I want to get at it for another interpretation.

The biggest problem I see with digital longevity is the signal-to-noise problem. It's so easy to keep thousands (or millions...) of captures, it becomes ever harder to find the far smaller number that are artistically worthy. I try to edit ruthlessly and organize my files logically, but I still worry that in a decade or two I'll be struggling to find that image I want to print again.

Posted by: Geoff Wittig | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 03:11 PM

Too much data is certainly a major issue.

Although I have all my images copied in triplicate on multiple hard drives, I can honestly say there are only a minute proportion of my images that I worry about keeping for posterity.

Hence, for digital, I have a top 1000 portfolio (actually 897 so far) converted to DNG. For negatives, I have about 200 scanned and saved as TIFFs. That represents about 0.2% of my output, but it's enough.

These are sufficiently small to fit on a handful of my older "slow" SD cards. Copies live with my family and friends and I recycle them periodically.

So far I have not lost a single item of data from an SD card, but I still make duplicates to be sure. CDs and DVDs are a lot less reliable in my experience.

Posted by: Steve Jacob | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 03:24 PM

I suspect that the people who care will back everything up and make sure shifts in format etc. get accounted for. These are the same people who would have prints and film in decent condition because they took care to archive properly.

Everyone else will lose everything the next time they get a severe enough virus infection or the hard drive dies, or might find they can't read the files any more (been there, done that). Actually these days it could happen if they drop their cellphone. In essence, their entire digital life is stuffed into a shoe-box in the basement, just like their now faded, torn and dog-eared photographs and fingerprint-plastered negatives were.

Digital's advantage is making it possible to create multiple perfect copies of the original, but only if you make the effort to do so.

Posted by: Paul Glover | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 05:37 PM

Dear folks,

Two broadly written thoughts, to address many people's remarks:

1) It is important to remain unconfused on theory vs common practice. All of you talking about how easily you can or can't preserve your film/digital photographs are failing to take into account that most people don't engage in those practices. This column was about what really happens, not about what you could do. Fact is that it's pretty easy to reasonably ensure huge longevity for digital photographs. It's even easier to ensure multi-century longevity for film photographs. (It's called a frost-free refrigerator and poly-sealed bags, and it'll work for everything except SX 70-style Polaroids. Proven technology).

But the overriding fact is that this is irrelevant because by and large people have not taken these measures and do not do so today. As I said, we're talking about what ordinary people do, and pretty much everything you're all suggesting is, as I said, extra-ordinary.

In that vein, I am not saying that things are in a good state now, digitally. What I did say is that I have reasons to think they will get much better, relatively quickly.

And, yes, William, the Film Era is over. That is a simple historical fact, based on preponderance of types. It's not an ideological point, it's a statistical one.

2) For all those who asked why it's even important to preserve this stuff beyond our immediate lives, well… for easily 90% of us it isn't, personally. That's anybody whose theologies don't have them fretting over what happened in their previous life after they die (that includes those who prefer the “null hypothesis”, since they won't be fretting over anything, period). For most of us, once we're dead we have no interest in what happened to our photographs; we either have other fish to fry or no fish at all.

(On the other hand, if you're one of the many people whose photographs haven't even lasted their present lifetime, you may be taking this question a little more seriously.)

The reason to care about what happens to your photographs after you die is because they may possibly be important to others, and you really have no idea what will or won't turn out to be important. When they were only five years old, who knew that Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton would end up being US presidents. I picked them because their childhood backgrounds are such that there is no obvious path to the White House unlike, say, a Kennedy or a Bush where it is at least plausible they would end up being "Someone Important."

There are huge chunks of history where we don't know a whole lot about how regular people lived, precisely because the records of regular people weren't considered worth preserving.

If you don't think this is important, fine. Then you're not one of the people who's worrying about how long their photographs will last and this whole column really isn't about you. Me, I'd rather have your stuff around than not.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 05:38 PM

Even the cheapest litho inks on acid-choked lignin-filled newsprint stock can easily last a century or more under reasonable storage, display, and handling conditions... and indefinitely if heroic measures were to be taken (e.g. low temperature storage). As is evidenced in many of the replies to this post, and in forum after forum, the real challenge is to know what those reasonable conditions are and to maintain them at all times. This outcome can only be achieved with a strong will to preserve. It's true of the analog era in photography, and it hasn't changed one bit (no pun intended) in the digital age. The less durable the product, the more narrow the range of "reasonable" environmental conditions one is required to maintain That's the reality of the situation.

Without active collection management activities and a deliberate effort to avoid as Mike says "the trough of no value", it's not just photographs that are vulnerable to loss. In fact, I'm hard pressed to think of any man made object where we couldn't be having the same discussion. So, perhaps it is because the fundamental EXPECTATION of the photographic process has historically been to function both as "memory keeper" and "memory sharer" which underscores so many peoples' concern about the intrinsic longevity of photographs.

Today, digital has shifted the functionality much more to easy share than easy keep, IMHO, even though many people advocate digital images are going to be easier to keep as well. I think the jury is out on that. The time span for the trough of no value to kick in and destroy digital records is very short. Meanwhile, I see a whole new generation of youthful picture takers who have imposed a remarkably low bar for image longevity. Their main purpose with photography is to post an "instant replay" of personal current events on social media websites. They regard the image as inherently temporal, to be replaced very soon by other more "up to date" moments in their lives.

All that said, when the goal finally shifts to "memory keeping" then image persistence, durability, longevity (call it what you will) becomes an issue worth paying some attention to. When things go wrong with those best laid plans for environmental safekeeping and come up short for extended periods of time, products that exhibit greater intrinsic resistance to chemical and physical deterioration are likely to contribute significantly more to their own chances of survival. Within any one process category (inkjet, for example) product durability spans a very large quality range, and there are many variables. That's why I study print durability issues, but I readily concede that many folks don't really care about print permanence any more, especially now that printing is no longer an essential component for sharing photographs.

regards,

Mark

http://www.aardenburg-imaging.com

Posted by: MHMG | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 05:52 PM

Dear Ed,

What you say is pretty much true, but do not confuse data and information. Data only matters if you're doing scientific record-keeping. Every restoration I do, of necessity, sacrifices some data. Really, any photographic manipulation does. But sometimes that increases the amount of information conveyed to the viewer. I have done occasional restorations where I know my restoration does a better and more complete job (for various meanings of those adjectives) of portraying the subject than the original photograph did. There are tricks I have to correct inherent deficiencies in original materials like poor tone and color rendition in print papers, for example.

I mention this, not because it's the norm, but it is just so bloody much fun when I can do a restoration that I can confidently say comes out better-than-new. It's a little like magic.

No, it's a lot like magic.

Except without that ever-multiplying marching broomstick thing.

~~~~~~

Dear Christian,

Thanks! I am unreasonably (although not unjustifiably) proud of figure 1; it was a real tour de force. In fact the original looks even more blank than the reproduction here; I haven't been able to come up with a scan and screen illustration that looks as faded and bad as the original did to my eye.

That photograph taught me to run a test scan on any photograph I was considering restoring, no matter how hopeless it looked. Those electronic sensors can see things that I can't.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Thursday, 16 June 2011 at 05:55 PM

I would only like to state that we should not confuse restoration (meaning of the original artifact) with a new digital or analog copy....this is more "recovery" -as a former photographic conservator I feel that we should be careful as sometimes only the information is needed....but conserving an original artifact is different that scanning it and using technology to "recover" the lost image..

Posted by: robert lyons | Monday, 20 June 2011 at 04:29 PM