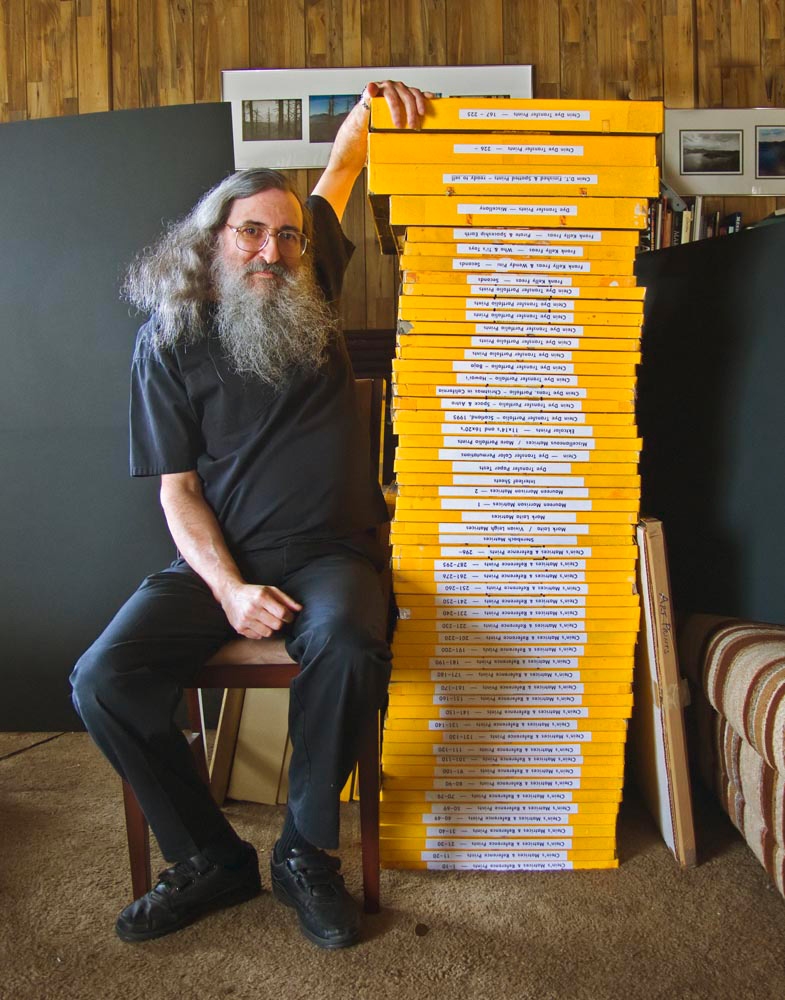

Ctein (it's pronounced "kuh-TINE") with some of his photographs

Ctein (it's pronounced "kuh-TINE") with some of his photographs

By Ctein

Welcome to the Bicentennial Celebration: This Is Ctein Column Number 200*! I felt like I needed to do something really special with this column. So, I'm going to mess with your heads. Lots.

Really.

If you thought my columns last Christmas were messing with your heads...

The Unseen Universe Gets Much Weirder (Very OT!)

...this time it's going to be a lot, lot worse.

Let me begin by explaining to you the idea of "local reality," a term used by physicists.

The first word is "local": in physics, this is actually a very strong word. For example, I can say the moon is globally a sphere, and you can confirm that for yourself just by looking at it. "Global" means that it's true taking the broad viewpoint. If I were to say the moon was "locally" a sphere, it would mean that it looks spherical at every size; no matter how close I got it would remain a perfectly shiny, perfectly spherical marble. "Local" means that we consider something to hold true everywhere, all the time, on all scales.

"Reality" means something very specific, but it's fairly commonsensical. Local reality has three characteristics:

• Causality: things happen for a reason. We may not know what the reason is, but still.... If my teacup suddenly takes off and starts flying around the room, I assume it happens for a reason. Maybe it's alien influence, maybe it's because someone put drugs in my teacup (I'll get back to that), maybe it's because I have poltergeists, maybe it's a miracle delivered to me personally by God. Something made it happen. It's hard to object to that.

• Objectivity: the things that we measure that we think are real really do have an existence independent of our imaginings. That teacup flying around the room? Unless someone has drugged my tea or I've gone insane, I assume it is there. If I make a photograph of it, I assume the photograph is real and what was photographed is real. If the tree falls in the forest, it does make the air move in a way we would hear as sound if we were there, even when no one is there.

(Lots of aspects of the world are subjective. If I ask you if you like pepperoni pizza, your answer is an objectively observable utterance, but your like or dislike of it is not.)

Like causality, objectivity is hard to disagree with. You can construct all kinds of philosophies where we are all living inside our own dreams or someone else's simulation, etc. But how many of us really believe that?

• Induction: this is a little more subtle, but we take it for granted. It's the belief that there is basically a logic to things. If we say that A always causes B and B always causes C, then A always causes C. Induction implies repeatability, which is at the heart of making any kind of an observation. I push the teacup off the table, and it falls to the floor. If I do it again (causality), and the teacup is really there and I really did push it (objectivity), then it should fall to the floor again...unless something has changed that causes it to fly around the room (back to causality).

That's what physicists mean when they talk about local reality, and it would be very hard for most of us to disagree that this is a quite sensible description of our basic experience with the world.

There's a slight problem. It's wrong. We can prove that the universe does not obey local reality and that at least one of our three assumptions has to be in error. We can do experiments in which things happen that are simply impossible according to local reality. I shall explain:

Simple logic can tell you how certain kinds of experiments will come out. Suppose I want to do a survey of cereal boxes in the supermarket. I'm going to count the total number of cereal boxes. Then I'm going to count the number of boxes that have sugar added. Finally I'm going to count the number of boxes that have no added sweeteners of any kind (those could be artificial sweeteners, sweet bits of candy or fruit, etc.; they might not be sugar). What can you tell me about the results?

It should be obvious that number of boxes that have added sugar plus the number of boxes that have no additional sweeteners of any kind must be no more than the total number of boxes of cereal on the shelf.

In general terms, Ctein's Inequality: [total items] is greater than or equal to [items with A] + [items without A thru Z]

This statement is not bulletproof. It does require some basic logic—those postulates of local reality. If the cereal boxes aren't really there or if counting them does not produce a predictable, reliable, and reproducible result, then my inequality can fail. But we would expect that in a normal, sane world, it will work.

Houston, we have a problem

Now, back to the world of physics labs rather than supermarkets.

Half a century ago, an amazing physicist named John Bell did this kind of logical analysis, figuring out what sorts of results we could expect from experiments. He came up with one called Bell's Inequality, a more sophisticated and useful version of my cereal box inequality. You can look up the details on the web. Its underlying logic demands nothing more than local reality; if that holds, Bell's Inequality applies.

In the late 1970s, a couple of physicists came up with a design for a quantum mechanics experiment that had an odd characteristic. They could calculate, using QM, what the results of the experiment should be. That prediction was in conflict with Bell's Inequality. So, of course, they ran the experiment! I do not know, but I strongly suspect that they were expecting to find a subtle flaw in quantum mechanics this way. No one thinks quantum mechanics is the be-all and end-all of physics, while local reality is awfully fundamental. So I imagine they believed the experiment would show some problem with their calculations which would lead to new, more interesting physics.

The universe threw them (and us) a curveball. Their experimental results matched their quantum mechanical calculations. The results were in violation of Bell's Inequality. In other words, the results were impossible if local reality were true.

Understand the import of that. This is not about whether or not quantum mechanics is right or wrong; quantum mechanics might very well be wrong in some way, although this experiment didn't find it. What this experiment said, though, was that local reality was unquestionably wrong.

Essentially, it was as if I had gone into the supermarket, did my cereal thing and counted that there were 38 boxes of cereal total, 23 of which had added sugar and 19 of which had no added sweeteners of any kind.

Houston, we have a problem.

First and most reasonable hypothesis: their experiment was flawed. Either their measurements were in error in some way, they were not measuring exactly what they thought they were measuring, or other factors they hadn't accounted for were intruding and messing up the experiment. That reasonable assumption hasn't panned out. In the intervening 30 years, the experiment has been refined dozens of times, and run by many different researchers.

With the advances in electronics and measuring devices, it's really at no more advanced a level today than college physics; it it might even be doable in a good high school physics lab. The results are pretty much bulletproof now—and they consistently violate local reality. Furthermore, people have come up with other experiments that measure different kinds of things that also violate Bell's Inequality.

So, it's not just one isolated case where local reality fails, although most of the time it works just fine. Regardless, reality is not supposed to be a sometimes thing. It means that we really don't understand what's going on, that our conceptual model is somehow fundamentally flawed.

So, which of our assumptions is wrong? Objectivity? Causality? Induction? Throwing out any of those makes reality a peculiar, disturbing, and very unfamiliar place. Yet we know that one of those (maybe more than one) isn't always true, it's just usually true.

Wild-ass guess

Physicists lean towards

throwing out objectivity; there's already been some thought for doing

that in both philosophy and quantum mechanics. But that's entirely an

emotional preference born of familiarity; we really don't know. Besides

which, throwing out objectivity raises those deep and nasty

philosophical questions like Schrödinger's cat, and what effect does an

observer have on the whole universe, and what does observer really mean

when we are all part of one universe, and even more

tie-your-head-in-knots conundrums.

Remarkably, physicists are starting to come up with experiments that can test which of those assumptions is wrong. That work is still in its early phases, and there is not entire agreement on the results, although it is looking like objectivity may be down for the count. Which, even if that's true, doesn't mean it's the only one of our assumptions that falls. If one of them is wrong, maybe all of them are wrong. Mildly scary thought.

What's truly astonishing, though, is that we are entering an era of experimental philosophy. Understanding the fundamental nature of experience and reality used to be limited to the great armchair theorists of our philosophy classes. Now people are actually figuring out physical experiments that may illuminate matters that we thought were entirely beyond the realm of experimentation.

Want to know my utterly wild-ass guess? I think, philosophically, we just plain have it wrong. I think we're in a stage akin to alchemy: we talk about things like "observers," "events," "measurements," and "objects" believing that these are fundamental components of reality. I think we're going to find out that they are philosophical Elementals, the equivalents of earth, air, fire, and water. They are undoubtedly real, but they'll turn out to not be fundamental building blocks of reality.

Like I said, wild-ass. And I wouldn't even try to guess what real philosophical "elements" might look like.

In 50 years, though, I think we will know something. Experimentation proceeds.

*(There is a bit of ambiguity in the data; technically this could be construed as anywhere between Column 198 and Column 202. By my arbitrary numbering system, it is 200. It's my party, and I'll cry if I want to....)

Ctein, a physicist by training, is a photographer, parrot aficionado, sci-fi fan, and—as the author of well over 500 articles published in photography magazines over five different decades—perhaps the most experienced phototechnical writer in America. His regular weekly column on TOP, not always confined to matters photographic but usually conventionally reality-based, appears on Wednesdays.

Featured Comment by Melv: "Eh?"

Ctein replies: I think "Whaaaaa???" might be more appropriate (g).

Featured Comment by Hugh Crawford: "I like the many-worlds interpretation with no wavefunction collapse , and not just because it was thought up by some other guy named Hugh (Everet). Flip a coin, create a universe unless it turns out that time is running backwards and you are consolidating two possible 'futures' into one 'now' I'm just glad to be in the universe where Ctein writes his off topic pieces about quantum mechanics and not golf. I just don't get golf at all."

Mike replies: It's harder than physics.

_files/patreon-2.gif)

Fun column Ctein, congrats on 200 give or take! Your column seems to indicate that our concept of reality must be flawed assuming we believe the results of the outlined experiment(s). Is it possible our concept of a reality that is local is flawed? That reality is not local, whatever the appropriate term for that is?

Posted by: Chris | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 11:44 AM

Fascinating, glad you went off topic for #200.

I'm curious to know more - what was the experiment the scientists in the 70s did to violate Bell's inequality?

Posted by: Steve Goldenberg | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 11:56 AM

There are a few errors in this article, and they are somewhat important ... not just of the nitpicking variety.

1. "Local" means that we consider something to hold true everywhere, all the time, on all scales.

"Local" in physics generically means something that we can assert for very small scales (technically infinitesimal) in both space and time. For example, general relativity treats spacetime as a manifold -- a mathematical object that is local flat everywhere but global need not be. This is the essence of the Einstein equivalence principle: one may locally remove gravity by moving to an observer that is freely falling. This does not mean that everywhere at all scales is flat (i.e. gravity can still exist).

When a physicist describes a (quantum) theory as local, they can mean one of two closely related things. The most common is a statement that call observables commute outside the lightcone, so that you cannot get faster than light influences from one observation to another. Technically this is called microcausality, but many physicists are sloppy. The other (which ensures microcausality) is that any interactions only couple fields at the same point.

The EPRB paradox satisfies "local" dynamics when described by quantum theory. The only time something non-local occurs is when you try and describe to the collapse of the wave-function -- something outside quantum mechanics (and it is not even clear that one needs it, as decoherence seems to be able to give us a world that to us looks classical without invoking any collapse postulates.)

Posted by: kiwidamien | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 12:20 PM

Oh dear.

Posted by: Jim McDermott | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 12:28 PM

2. "Induction"

The argument that A implies B and B implies C is known as syllogism, not induction. (It is used an infinite number of times in the principle of mathematical induction, and some philosophers are not convinced that an infinite chain of syllogisms are meaningful.) This is not under attack by physics in any way, shape or form, as the truth of syllogisms are at the heart of your formal logic system.

Physics at its heart is an experimental science. We don't have any statements that we know about the world (i.e. not just to do with our formal logic system) that we know to be true. For example, we don't know that "Energy is always conserved". We have seen it conserved in many experiments before, so we write down our theory in which this is one of the rules. Because we have not done all possible experiments, we may have to replace that rule eventually with something else. The more experiments we do, the more confident we are that the rule really is a law of nature, but we can never *know*. This process of making a set of observations that is true, and postulating that it is always true is sometimes called induction, but it is an assumption that is always up for revision when a counter-example rears its ugly head--it is not a logically bulletproof statement!

The conservation of energy is a good example: for all experiments on Earth we have found that energy is conserved to the accuracy of the apparatus. But when we started to learn more about cosmology and general relativity, we found that the expansion of the universe meant that the total ("global") energy was not conserved, and had to revise our rules. The "local" energy density is still conserved, and we have (yet) to find any counter-examples.

Posted by: kiwidamien | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 12:32 PM

I would agree that we are entering interesting times, but so far my money (for what it is worth) is on quantum mechanics being the whole picture, and in large systems the wavefunction never collapses but decoheres into almost-classical parts with very little interference. That would leave all three postulates intact, and would require no new physics. Indeed we have something of a 'god-of-gaps' at the moment, as decoherence is used at all the levels we have been able to study systems so far (almost up to the scales of viruses!) but the claims are "maybe things are different a few scales up!".

I would appeal to scientific induction (the one that is not logically bulletproof, but allows us to progress with only a finite number of observations) and claim that after making so many observations that I need a reason to hold out on decoherence being the only solution.

I would disagree that now we are entering the age of experimental philosophy. Physics has been doing this for years. Aristotle postulated mechanics based on how he thought the world should work -- work that was toppled by the experimentally driven Newtonian mechanics. We thought that we were the center of the solar system, with the orbits related to the Plutonic solids. This idea was thrown out by observations by Kepler. Einstein (and others) held onto the idea that the universe as a whole was static and unvarying -- Einstein even introduced the cosmological constant into general relativity to achieve a static universe that was impossible in the first version of his theory with known matter -- until Hubble's observations showed that the universe was indeed expanding.

Physics has been digging deep into the nature of reality, and challenging philosophy for almost 300 years. This is another interesting example of it, but by no means the first or marking the beginning of an era.

Posted by: kiwidamien | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 12:48 PM

Mayhaps those constructivists we've always pooh poohed are onto something after all?

Posted by: russell | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:01 PM

Wherever you are, there you are.

Posted by: charlie | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:03 PM

Or we may find that Plato was right all along about his Forms. Certainly fits how I approach photography. The camera is seeing something, right? If that's questionable I'm giving up and going back to music.

Posted by: Mel | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:12 PM

Reality might be overrated, but it's the only place where you can get a good steak, no?

Posted by: erlik | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:18 PM

PS. I guess the rest of the comments will be similar. :)

Posted by: erlik | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:19 PM

We take it for granted that a dog cannot understand, say, how a camera works, or philosophy, or art, or what those little bright dots in the night sky actually are—even when we explained it to him. However we tend to believe we can understand anything if we only think hard enough. But while our brains are bigger than our dogs', compared to the size of the universe they still are pretty small objects. I guess reality includes concepts that simply are too big for us to get our heads wrapped around—it's not just a matter of doing more research but a fundamental limitation of what we can possibly think. Dogs' brains are limited ... so are ours.

Posted by: 01af | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:24 PM

You lost me at "Welcome to..."

Seriously, though. Great article.

Posted by: Scott | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:41 PM

Your WAG is the most comforting view I can think of. Accepting our basic philosophical view but rejecting some of those principles is deeply troubling.

My philosophical comfort may, of course, not be high priority for the real world.

Posted by: David Dyer-Bennet | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:50 PM

This is very interesting, but I have to wonder: If there is sufficient reason to question objectivity, causality, and induction, doesn't that create problems for scientific method itself? And if so, how can scientific experiments be designed that could really get to the bottom of all this? If there is an explanation that a non-physicist, non-scientist such as myself could understand, I would be curious to know.

Posted by: Alex Nichols | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:55 PM

42 boxes of cereal.

42.

Hmmm.

Aha! Douglas Adams had it right (that and so much else) in "The Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy."

Perhaps he's the man behind the "Ctein"?

Patrick

Posted by: Patrick Snook | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 01:57 PM

At some point, very close to where we are, irrelevance sets in.

Posted by: John Camp | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 02:04 PM

Ctein:

What's the name of the experiment / experimenters you are referring to?

I think that counting the boxes multiple times is the problem. Ask any chicken farmer how well that's going to work.

I'd go with Lisa Randall ( I used to argue with a coworker whether she or Lene Hau* would be the physicist we would most like to go on a date with ) and say that what we think about time and or space has more to do with how our minds work than how or whether time or space exist.

Of course if time turns out to be a human construct, then causality goes out the window along with free will. I.E. if the teacup is going to fall off the table then something has to push it, and that something turns out to be you, but there needs to be a reason for you to push it and it turns out that it was thinking about causality.

*Lene Hau can stop and restart light but Lisa Randall calls into question whether it was going anywhere to begin with. Like I said I'd go with Lisa Randall but that's sort of a Ginger vs. Maryann kind of choice.

Posted by: hugh crawford | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 02:11 PM

It has been a while since I looked at this stuff, but if Ctein is talking about the experiment I think it is with Bell's inequality I understood the experiment to show that wave-particle duality idea is false. This is roughly that fundamental particles such as electrons can sometimes behave like a particle and sometimes like a wave, but never at the same time. The Bell's Inequality experiment caught it doing both.

This was central to the Copenhagen interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, which had various other theoretical problems that were ignored until this nail in the coffin.

The result is that currently no one can "explain" what happens at a quantum level, but can calculate the result of whatever happens. Perhaps this is what Ctein is getting at, otherwise I'm really confused.

In any case, I rather thought everybody had been in agreement for a long time that quantum theory (in some form or other) is pretty fundamental and this "local reality" business was binned a long time ago!

Posted by: ScottF | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 02:26 PM

if you have time, have a look at these two papers: http://dx.doi.org/10.4006/1.3231944

(also available from http://neuron2.net/QM/bell.pdf ) and http://bayes.wustl.edu/etj/articles/cmystery.pdf

The basis of the problems with the non-causality or non-locality lies in the foundations of probability theory, not in QM!

In a nutshell, probabilities are NOT physical. Rather, they attach to logical propositions in a given domain of discourse,

In this view of probability (due to Cox and Jaynes) there are no random quantities in the traditional sense, only "knowns" and "unknowns" (Example: Schrödinger's cat is either dead or alive, not a zombie. A coin only falls on head or tail, but nothing in between.) Over the "unknowns" we specify a probability distribution to characterize the *state of knowledge* about the unknown quantity. But this state of knowledge is not physical, it is logical.

On a side note, this contradicts both the frequentist view (who say the data are random while the parameters are constant ) and the standard Bayesian view (which assumes random parameters and constant data).

For the Bell theorem this implies that there is no physical non-locality, only a logical non-locality. Causation is tied with physical locality, so the mystery dissolves.

More info on the Cox theorem here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cox%27s_theorem

Ed Jaynes has written a book on his view on the foundations of probability theory which unfortunately appeared only after his death:

Jaynes: Probability Theory, The Logic of Science ( http://www.cambridge.org/de/knowledge/isbn/item1155795/)

If you find the time, read this book, it is is certainly among the most influential science books of the last century (and this one too)

Posted by: Sebastian Schanze | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 02:27 PM

If you KNEW you wouldn't need wild ass guesses.

Posted by: Doug Dolde | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 02:43 PM

So.....

A really excellent optical illusion or hologram may appear to be completely real, but if you know what you are looking for you can observe that you are being tricked. Without knowing about the existence of a trick, or knowing what tell tale signs to look for, your observations of the illusion are not exactly wrong, but are wholly incomplete and misleading.

And you're saying that the entirety of the sciences are, almost certainly, being completely misled by some tricks of observation which are so pervasive we can barely find any tell anywhere in our universe. Except for those few really big tells which imply everything we know about everything is a mere fraction of the truth.

Life is fascinating.

Posted by: ILTim | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 03:19 PM

Yah...OK...Sure...

...but, I prefer my physics to be Useful as well as thought-provoking!

http://www.youtube.com/user/cubert01?v=gidumziw4JE&feature=pyv&ad=6610675043&kw=of

;~)

Cheers! Jay

Posted by: Jay Frew | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 04:11 PM

That dog may not understand man's explanation of the things which man considers worth trying to explain but it is entirely possible that the dog may understand, to its own satisfaction, another dog's explanation of the sort of things that dogs think about and then sleep well and die happy, which is a good goal for both man and dog.

Posted by: Len Salem | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 04:38 PM

Hi Ctein.

Congats on the 200th.

I wasn't going to post but the next site I went to was a blog about a book of the History of Space Art you might have an interest in, so here it is;

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/badastronomy/2011/08/17/the-beauty-of-space/

I like how CGI has made cosmology, dinosaurs and sci-fi cool as it was a lot different when I was growing up. Hasn't made it any easier to understand though!

Posts like yours remind me of Asimov's "The Final Question", or Poul Anderson's "Tau Zero", but cosmology is fascinating but incomprehensible to me; I still go wow! if I see the ISS or a meteor:-)

I reckon there is a strong affinity between telescopes and lenses as a site I go to quite often with anything from astrophotography to AFV telescopes is Pete Albrecht's;

http://www.petealbrecht.com/blog/blog.htm

which would repay a few hours scrolling through.

Just found this that made me laugh;

http://www.chrismadden.co.uk/science-cartoons/large-hadron-collider-cartoon.html

all the best phil

Posted by: phil | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 05:31 PM

So this is what DSLR's dream about, until we turn them on and force them to take pictures for us. Explains why they cost so much.

Fortunately, I use a 2004 model (and my girlfriend is a retired exotic dancer)

Great article, though, Ctein, brings me back to Poul Anderson and multiple parallel universes, metaphysics..fun in life!

Posted by: Ben Ng | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 05:35 PM

To quote Star Trek:

"It's worse than that Jim, it's physics!"

Posted by: Tony | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 08:17 PM

You know what's cool? Somewhere around "Houston", you can just click over to Domai real quick for a breather and then come back.

Posted by: Marty | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 09:00 PM

This isn't OT, it is a preamble to a very ON-T part 2 which discusses the implications for photographic philopsophy, i.e. is the emphasis on photos having to depict and not distort 'reality' overrated?

Posted by: Arg | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 09:34 PM

I just told my spousal equivalent: "Not tonight, I have a headache".

Posted by: Dave Kee | Wednesday, 17 August 2011 at 10:27 PM

"...quantum mechanics might very well be wrong in some way, although this experiment didn't find it. What this experiment said, though, was that local reality was unquestionably wrong."

Now here's the thing: people have been trying to break QM for almost 100 years. Guess what? No one has done it. Of course they will keep trying to break QM... and this is a good thing. I'm just glad my career didn't hinge on attempting to find a flaw in QM.

Unfortunately for humans, intuition is essentially useless when it comes to QM.

Richard Feynman said:

"Do not keep saying to yourself, if you can possibly avoid it, "But how can it [QM] be like that?" because you will get "down the drain," into a blind alley from which nobody has yet escaped. Nobody knows how it can be like that."

Posted by: William | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 12:47 AM

Sorry to keep posting.

But Sebastian's post is relevant and insightful.

Of course parameters (what we estimate) such as the number of photon captured by a given digital sensor site during an exposure, can be random and the data (what we want to measure) is constant. Who knows what the real, but unknown value of a parameter is... ever. The best you can do is estimate a value for the parameter and some estimates are more certain than others. Just because the data is noisy, i.e. a measurement value has a high degree of uncertainty, doesn't mean what you need to measure (data) is random. Suppose 9 electrons are generated by photos interacting with a digital sensor site and the total number of electrons at the same site due to noise fluctuates between 6 and 1 photons for each exposure. The data – or the real, but unknown, number of photons – is constant (9). The uncertainty (which is not data) or noise is not.

Probability theory languished on the back burner for decades because computing probability density functions for meaningful problems was impractical. The advent of inexpensive parallel computing means Probability Theory will eventually replace Frequency of Occurrence statistics. Fields like astronomy (where the very best measurement have a high degree of uncertainty) are already heavy users of Probability Theory.

Ed Jaynes book is a master piece. Even if you skip over all the math, you will never think about statistics the same way after you read Jaynes book.

But don't read Jaynes book if you believe shooting in RAW is unnecessary. JPEG shooters will be much happier if they never read what Jaynes says about discarding, modifying or filtering original data. The same goes for people who believe noise reduction is literally possible. You really don't want to read Jaynes either.

Disclaimer: I worked closely with Larry Brethorst who edited and published Jaynes book.

Posted by: William | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 01:56 AM

Uhm... I just wanted to read something about high ISO ...or something. And go to bed.

Now I am wondering whether I really 'am', since I know that I, at some point this morning anyway, 'was', but now, uhm... where was I?

Not a dull day at TOP. Keep it coming - just reserve these articles for those days when I happen upon them in the morning.

Posted by: Tee | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 02:09 AM

Even if the physical theory aspects are discounted, there are still purely logical difficulties with notions of external reality vs our (joint and several) internal concepts and beliefs about reality. We can tie ourselves in nasty knots about whether or not we can safely trust evidence from our senses (many teenagers experience this worry at some point, if they are at all thoughtful, before sensibly setting it aside), and whether the actuality of evidence of something (assuming we don't doubt it altogether), resides in the evidence or in the something.

If at all interested in these considerations, which in daily life we can't afford to be [grin] - the most clear-minded and lay-accessible discussion that I have encountered is that by Gilbert Ryle, in for example "The Concept of Mind". Donnish, dated in style, yet elegant almost to a fault.

Posted by: richardplondon | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 05:11 AM

I make no claim to understanding contemporary physics other than to say that the world that we think we know and which forms the basis of our daily dialogue is at best a weak anthropomorphic representation of that which really is and at worst a complete misunderstanding of reality which itself may not actually exist. This quandry informs and is the basis of my photography which, if you're interested, you can view at http://www.ericperlberg.com.

Posted by: RelentlessFocus | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 05:51 AM

Heck with the column, nice picture!

Posted by: Crabby Umbo | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 06:21 AM

Yep. Sounds good to me. Can't say I disagree with anything in the post.

Posted by: David H. | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 06:57 AM

Hi Ctein,

great text - should i be worried if i find this much less 'messing with my head' than some of your past columns?

As a sci-fi fan you probably approciate today's wikipedia featured article which is about another 200th celebration (probably some kind of quantum entanglement going on there...)

Posted by: Chris | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 07:54 AM

Dear Hugh,

I am at Worldcon, so I can't pull the experiment dates. It is late 70's; a good article appeared in Scientific American in 1979 (I think).

~~~~~~~

Dear Scott,

So, yes this is old news... But not to most lay folk. And, I would agre with you that this is a long firmly-settled matter... But there are very good minds who disagree. The "philosophy" of QM, as opposed to the facts, is still hotly and properly debated, even though I think the consensus is clear. For example, read "kiwi"'s excellent set of posts. The only reason I am not commenting on them is that I think they should stand free, and it would raise the level of discussion to incomprehensibly stratospheric levels. Very much not what Mike wants the comments to be for. But do give his three posts a very close read.

~~~~~~~~

Dear William,

...and continuing... Feynman is both right and wrong. We don't know why the formalisms of QM work, haven't for over fifty years. It is vexing to do physics and not have any really good idea of why it is working. So you just have to put that aside and move on with your life. OTOH, Feyman got his Nobel prize out of a failure, from his perspective. He did not solve the problem of the electron singularity and he did not come up with a methodology that made QM intelligible. He just came up with something that worked fabulously well.

Feynman could also be flat-out wrong. He poo-pooed experimental particle physics as something utterly incapable of giving us any real understanding of the universe. History has quite firmly disproven that assertion.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: Ctein | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 01:26 PM

I read this yesterday and meant to post (and today I expected to see someone already say this): I read the headline 3 times, each time seeing it as "Ctein's 200th Column Really Is Overrated". Which I thought odd... why post if one knows its overrated? Then my brain started working again.

Patrick

Posted by: Patrick Perez | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 02:09 PM

I recall watching a car moving along a road.

I had a sense that the wheels were not turning but only seeming to turn - dependent upon me appreciating a succession of moments.

So I will go with causality being the weak link.

Posted by: David Bennett | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 04:06 PM

I've always wanted to see an article in the popular press about Bell's theorem. Thanks

Posted by: Joseph Kashi | Thursday, 18 August 2011 at 06:19 PM

I believe scale has a lot to do with it Ctein, predictatbility exist in the same relative demensions as the observer. So in the world of real life physics (call it locality or call it scale) the universe seams to be a really big but sort of calm and predictable place (even a supernova can be more or less predicted). But strip away the venear and underneath you find the unpredictability on the small (quantum dynamics, dark matter, dark energy) and the very large scale, for instance branes and the mirror edges of time and space itself. Great post though, and if any of you would want to dive into this stuf, try a Brian Green book.

Greetings, Ed

Posted by: Ed | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 03:52 AM

Trying to figure this raeality stuff out myself. Closest I've come is The First and Last Freedom by Jiddu Krishnamurti. Constant awareness from moment to moment. There is an interval between two thoughts. The observer is the observed.

Posted by: Simon Griffee | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 08:10 AM

And for your next 'mind messing' column, how about TIME: direction? dimensionality? existance? the tachyon and time travel?

and then there's String Theory....

Maybe for Xmas (whenever that is, if it is

Posted by: Richard Newman | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 10:13 AM

Once and for all, is there or is there not a rhinoceros in the room?

Posted by: TimA | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 10:52 AM

A few years back, I was reading about Bell's Theorem, and I was reading about the experiment. I read it, then read it again, not understanding. I read it a third time, stopping after each small explanation of the states of the tangled photons, and then all of a sudden I understood what it meant. And I was in awe. If locality is an illusion, then everything is all actually one big thing. Size, space, everything is a product of our understanding and perception; the universe is actually a singularity.

And then I was hungry, so I made a sandwich.

Posted by: Tom Brenholtw | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 12:38 PM

"how about TIME: direction? dimensionality? existance? the tachyon and time travel? and then there's String Theory...."

Or, he could consider a column called "Mike's Patience for Physics Columns on his Photography Website: Is It Infinite? Not." Just sayin'.

Mike

Posted by: Mike Johnston | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 01:12 PM

Sir:

Huh?

Paul Richardson

Posted by: Paul Richardson | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 02:04 PM

Dear Mike,

Careful- I am fully prepared to start the series on the Art of Tea.

pax / caffeinated Ctein

Posted by: Ctein | Friday, 19 August 2011 at 09:04 PM

A neutron walks into a bar and orders a beer. The bartender says: "For you, there's no charge."

Posted by: Paul Baur | Saturday, 20 August 2011 at 12:49 AM

"Or, he could consider a column called "Mike's Patience for Physics Columns on his Photography Website: Is It Infinite? Not." Just sayin'."

But Mike, all of photography IS just physics - from the electrons which illuminate the subject to the electrical churning in the brain which with which we interpret and evaluate the image (real or virtual). No physics, no photography

Posted by: Richard Newman | Saturday, 20 August 2011 at 03:51 PM

Richard,

You can see the physics in it, I'll see the poetry. It's that multivalence that makes it so interesting.

Mike

Posted by: Mike Johnston | Saturday, 20 August 2011 at 03:55 PM

I've decided I am going to name my next cat "Schrödinger"

Posted by: Rip | Saturday, 20 August 2011 at 07:37 PM

There is a science-fiction series I like wherein one of the alien races man encounters has a group of people (later there are human ones) called "sohon masters," who can manipulate matter at the quantum level with their minds. (Humans, being humans, refer to them as "mentats.")

At one point, one of them is trying to explain something to a reasonably bright human (who isn't a physicist but can hum a few bars.) She says, "You understand that the famous equation E=mc^2 means that matter and energy are forms of the same thing and they can be converted into each other. That understanding is completely and fundamentally incorrect. However, it's a useful metaphor to explain the observable effects of what's really going on."

That's all physics (and most other sciences) are: useful metaphors. Newton's equations of motion, even though we've known for decades that they're totally wrong and never, ever give the right answer to any problem, are such useful metaphors that we still use 'em, blissfully unconcerned about the relativistic/quantum mechanical errors that they allow to creep into our every calculation. :)

Our metaphors, they will get better. However, sometimes I wonder if it isn't kind of arrogant of us to think that we *can* understand, that someday we will know the "truth." I think we can certainly find a metaphor that will accurately describe the observable universe to the limits of our detection. But the problem is we'll never know if the universe is finer-grained than our detection ability. :)

Posted by: MarcW | Monday, 22 August 2011 at 09:58 AM

Induction is logic. Logic cannot fail. Ask Spock.

Posted by: Richard Man | Monday, 22 August 2011 at 05:12 PM