This week's column by Ctein

I know I've been neglecting my off-topic obligations (if they can be called such). Just too much good photographica to write about. Finally, here's another one (and there'll be a second part in two weeks). For thems of you whats hates these, come back next week for more of my photobabble.

Miles O'Brien, PBS Newshour science correspondent, interviews an expert panel on the history of the Johnson Spaceflight Center and NASA.

Miles O'Brien, PBS Newshour science correspondent, interviews an expert panel on the history of the Johnson Spaceflight Center and NASA.

Last September, Houston was the site of the first "private" 100 Year Starship (100YSS) conference. The previous year's 100 Year Starship conference was a DARPA-initiated government conference. You can read my report on it. This year's conference was the first hosted by the 100YSS Foundation, established with a DARPA grant of $500,000 after last year's confab. The reason for the quote marks around "private" is that anybody could attend; you merely had to pay the conference fee.

As I explained previously, DARPA doesn't build stuff. They spark interesting and innovative endeavors and then they throw a little money at private entities to kickstart the thing. Their interests are national security and defense, staying ahead of the rest of the world's technology curve. Forty-something years ago, they envisioned it might be useful for the Defense Department to have a robust and distributed communications network in case war broke out. The result was something called ARPANET. Ever heard of it?*

The 100 Year Starship is considerably more ambitious. Its goal is, over the next century, to either build and launch a starship or to establish the technological, industrial, managerial and economic base that would be capable of doing so. DARPA doesn't especially want or need a starship. The myriad instrumentalities and technologies required to build such an amazing endeavor, though, would transform U.S. science, production, and manufacturing even more radically than the Moon Race did.

Unfortunately, the path to the stars is much longer and much less clearly defined than that to the Moon. I truly cannot speak for all 250 attendees, a substantial fraction of whom were at the first year's DARPA conference, but my sense of it is that the consensus feels similarly: we all hope this venture will succeed, and we all expect this first attempt won't. There are too many ways it can go wrong, too many mistakes that can be made. It would require great luck for none of them to prove fatal to the enterprise. But, one has to start somewhere, and the objective is to learn enough so that if the 100YSS fails to achieve its goal, the next attempt will fare better.

Which still leaves the problem, how do you do this? More specifically, at this early stage, how do you build an organization that could attempt to do this?

I'm sure that's the problem DARPA faced when they looked over the request-for-funding proposals from last year's conference. I heard that there were close to three dozen submissions. Among the half-dozen top ones, I doubt there was a single one that wasn't worthy of funding. They ranged from "let's start cutting metal tomorrow" (only a modest exaggeration) to "the problems are still so ill-defined that we shouldn't jump into anything."

DARPA decided to go the latter route and awarded the grant to the proposal from Dr. Mae Jemison (see my previous column) and The Jemison Group. In six months they managed to go from getting the grant to pulling off a major conference. I know a little something about throwing conferences. When you're running that fast there will be problems, and there were a few, but it gets a solid B+. These people are very good at moving fast. Not so incidentally, the 2013 conference will be held in Houston this September. I plan to be there.

What did this first conference accomplish? Well, now, that's an interesting question. Content-wise, very little. That has some people frustrated (especially the cut-metal set). My take on it is that this event was mostly about process—setting up the sociological constraints and boundary conditions that would facilitate getting to concrete answers down the road. (Most interestingly, I realized that this conference bore substantial similarities to a project I was involved in over 40 years ago. More on that next time.)

I'm not privy to the inner workings of the 100YSS Foundation or their agenda. Three process goals, though, were clear to me. The first was to create an intellectual "big tent." When you aren't sure what the right approach to a problem is, you don't want to be rejecting possibilities and talents out of hand. You never know what you'll need later. You explore as many avenues as possible, in parallel, and try to avoid tossing any out prematurely, just because one seems most promising at the moment.

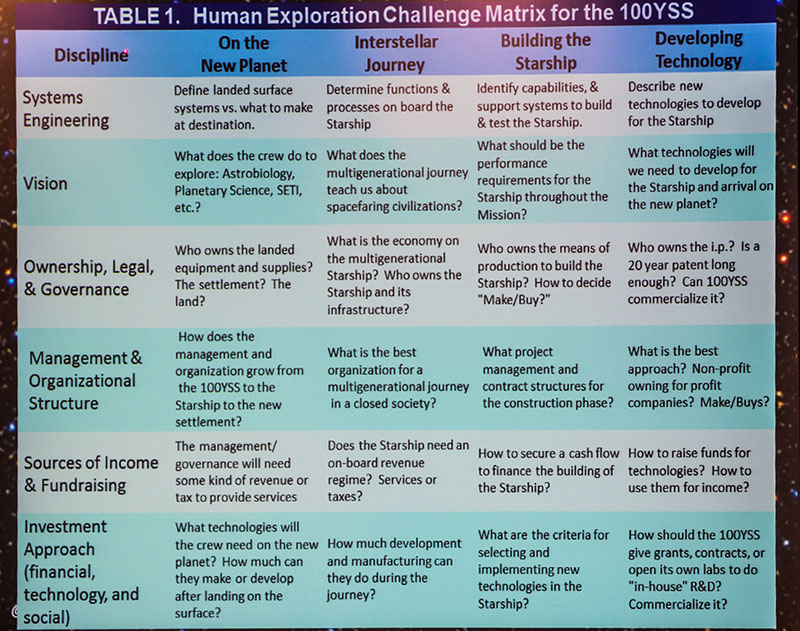

So many questions, so few answers. One

speaker's take on just some of the matters that

will need to be addressed to make the 100YSS

project a success.

So many questions, so few answers. One

speaker's take on just some of the matters that

will need to be addressed to make the 100YSS

project a success.

Sounds good in principle. In practice it can be dicey. For one thing, most people need focus to accomplish anything. If the immediate problems and goals seem impossibly diffuse, it's difficult to get anywhere. It can also lead to mission creep, where the goal perpetually mutates in ways that have people spinning their wheels, or leads them down a garden path they never meant to follow.

It's also frustrating to the people who have a clear idea in mind of how the problem should be solved (whether or not they have the best answer). They want to get moving on a solution and tend to be impatient waiting for the Big Plan to jell. Entirely understandable, unfortunately. You have to figure out ways to keep those people happy so they don't leave in frustration.

In fact, several autonomous subgroups spontaneously appeared from within the conference attendees—like-minded people who are trying to pursue their more immediate goals without having to wait for the entire operation to arrive at consensus. I have this suspicion that the Foundation expected that to happen. As I said, a big tent.

You're also at risk of infiltration by nutters and crackpots, and you want to make sure they can't hijack the agenda or appear to be representative of the group. We had just a couple of those. I would say that most of the people at the conference, though, were a lot like me: smart, educated, with a hard head and a practical mind, and open to new ideas...but with large bullshit filters. It's harder to hijack a group like that. Still, it's a possibility that I'm sure the Foundation is wrestling with, because circumstances can change, and dealing with this potential problem is a complicated process issue.

None of which is to say that the "big tent" is the wrong approach. Personally, I think it's the only one that has a chance of working at the present time. That doesn't mean it isn't fraught with peril. We'll see how well it works out.

The second goal? I'll get to that in the second part of this column, in two weeks. A hint—when I said the people were a lot like me? In some very important ways, I lied. Ah, the anticipation....

©2013 by Ctein, all rights reserved

*Satire alert

Original contents copyright 2013 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Hugh Crawford: "The Ownership, Legal, and Governance part is the most interesting. It sure won't be capitalism as we know it."

John Camp: "I find the concept fascinating, as much for the management problems as for the actual development of a starship. Cutting metal at this point seems absurd, when you don't even know who or what would go to another star. To send off a crippled mission in ten years that wouldn't even be able to report back before it was obsolete seems foolish. (For example, you have to decide exactly what you'd want such a mission to return in the way of results—but the earth-orbit astronomical telescopes are now returning such a wealth of new information that it would seem to me most profitable to try to expand their capabilities, and in x number of years you might be able to find out much of the information that you'd get from an actual probe. I mean, do we really want to spend trillions to send a starship out to a place if it reports back in two hundred years that the target planet is another Mars? In other words, close, but no cigar?)

"It's a great thought problem, though, and would take excellent management just to catalog the relevant thoughts.

"But—$500,000 is trivial. In fact, it's so trivial, that I suspect most of it will be wasted. $500,000 per year might get something done, but not much—that might buy you a three or four-person staff. What we need to do is get rich SF writers, and there are at least a couple of dozen of those, to kick in a tax-deductible 5% of their income to a starship fund...."

%20How%20Do%20You%20Build%20A%20Starship-Building%20Organization%20_files/patreon-2.gif)

I used to be such a starship dreamer in my youth, and now I just wish DARPA and other federal agencies would introduce a 100 year plan to deal with man-made global climate change. The science can be just as cool, just as revolutionary as a starship, is so needed. NASA at least seems to be increasingly brave about telling it like it is... http://climate.nasa.gov/

Posted by: John Krumm | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 01:37 PM

Don't Richard Branson and Elon Musk own space now? Good luck getting space away from those two nutters. I heard Musk is already has a working Klingon Bird of Prey he bought from a couple of Ferengis.

Posted by: Taran | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 01:43 PM

Imagine how the 100 year Starship passengers will feel when, a few years in, the 10 Year Starship goes whizzing by!

Posted by: Dennis Moyes | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 02:53 PM

...the funny thing is, we are already on a starship...

ARE WE THERE YET?

Its the journey not the destination right?...

Posted by: robert | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 03:32 PM

Dear Dennis,

Yes, this is known as the “Far Centaurus” problem. There was at least one paper presented on this at the DARPA conference (possibly several, but I could only be in one place at a time).

What this basically boils down to is that for any given projection into the future of improving technology (in this case, speed), you can find a “sweet spot" that is the optimal time for launching. If you launch much before or after that sweet spot, your ETA becomes later than it would be if you launch in that window.

As an end-point example, if we had to we could build an interstellar “space ark” that would launch in 15 years (I cannot imagine any reason why we would have to, this is a thought experiment). With existing technology, though, we could not plan on a travel time to any reasonably nearby star of much less than a millennium.

So what's the likelihood that in, oh say the next 500 years, engineering improves enough that we could make that same trip in less than half a millennium? Pretty good, I'd think.

Related to that, if you're being really serious about a 100 year starship program, you don't want to be nailing down the hardware and mission constraints for at least 50 years, if you can avoid it. It's a lot like buying a new computer or digital camera; a certain amount of procrastination is a virtue.

~~~~

Dear Robert,

You can go buy 10 round-the-world airline tickets today and fly until your butt is sore.

That doesn't mean you've gone to the moon.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 05:39 PM

The impossible dream?

http://thearchdruidreport.blogspot.com.au/2011/08/elegy-for-age-of-space.html

Posted by: Mart | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 07:48 PM

I think this is a waste of time and money.

1. Unless we can radically change human nature, I don't believe it will be possible for a crew to stay friends for 100 years, especially when procreation must necessarily be involved. It doesn't matter what the circumstances, humans just can't get along with each other long term.

2. Technology is moving so fast that a simpler, better, cheaper way will be found within the first 50 years. How are you going to tell the 100 year crew that their mission is superseded? That there'll be a welcoming party at the destination. Or that a far better candidate planet was found 50 years ago, so we changed our minds.

3. No matter what we do, things break down. How are we going to do major repairs so far from base? How many spares can a ship carry?

4. No-one yet knows how to 100% protect from space radiation, high energy particles and micro meteors.

5. How are you going to keep the next two generations, maybe three, on the star ship "on mission"?

I could go on. I don't believe humans are physically capable of travelling these huge distances and times. There will be a solution involving some quantum mechanism. We just have to keep ourselves alive here on Earth long enough for the answer to present itself.

Don't forget, 100 years ago radio was just being invented and electronics was unknown. New technologies we've never even thought of can spring up to solve problems like this. Let's work on more practical problems. This is a waste of our limited time and money.

Posted by: Peter Croft | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 08:34 PM

I had access to ARPANET in the '70s when our lab was one of the approximately 200 university and gov't labs with access nodes. How time flies,,,

As for the 100year time frame, thats because of the human cargo. We could probably send a robotic ship to alpha centauri (about 4.4 light years) in a decade given the resources =$$$. It could make a round trip in 20-30 years, including time on site. But humans can't survive the same level of g forces as a machine, and we require things like food and air, all of which create size, weight, and other penalties. So the manned ship will take much longer, which makes support even more difficult. Hence, the long development lead time. And we can't count on wormholes to speed things up. But we gotta start some time if we're going to do it.Lets hope its now.

Posted by: rnewman | Wednesday, 01 May 2013 at 09:54 PM

Either we need to focus on fixing our current starship (aka Earth) or we need a bunch of starships to bail out of here before all the systems finish crashing.

Give the planet a few millennia of R&R and it could be habitable again, preferably by an intelligent species.

Posted by: JackS | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 09:04 AM

"Most people need focus to accomplish anything. If the immediate problems and goals seem impossibly diffuse, it's difficult to get anywhere. It can also lead to mission creep, where the goal perpetually mutates in ways that have people spinning their wheels, or leads them down a garden path they never meant to follow."

This is why I dropped out of a PhD in image processing for robotics and became a full-time photographer.

Posted by: Josh M | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 09:26 AM

What's the point of a manned mission? We're sending robots to a) Mars and b) the bottom of the sea. Why in the world not send unmanned probes to other solar systems, provided anyone could see a need to do so? Is the goal colonization here, and, if so, why?

Mike

Posted by: Mike Johnston | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 09:49 AM

"fatal to the enterprise", Ctein?

Is there something you're hinting at that you can't say outright? A paradox, crossing of time streams, or something to do with the Prime Directive, perhaps?

Posted by: Ken Jarecke | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 11:19 AM

"Most people need focus to accomplish anything. If the immediate problems and goals seem impossibly diffuse, it's difficult to get anywhere. It can also lead to mission creep, where the goal perpetually mutates in ways that have people spinning their wheels, or leads them down a garden path they never meant to follow."

The same can be said of being an artist.

Nothing like committing to an exhibition a few months or a couple of weeks in advance then figuring out what to do.

The "leads them down a garden path they never meant to follow" part is a good thing in my opinion. In both art or science if you know exactly where you are going why bother?

Posted by: hugh crawford | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 01:18 PM

Dear John,

Regarding the $500K, quite so. As I said in my previous column, DARPA is an enabler. What they hand out is seed money. Part of their criteria are the ability to develop funding. I could have submitted the absolutely perfect starship proposal, engineering-wise, and they would never have given me the money. Not unless I teamed up with some entrepreneurs or vulture capitalists with a very good track record for this kind of thing.

~~~~

Dear Peter,

Please go back and reread the previous column, because many of your points are addressed in that column and especially in the comments that follow it.

That said, you haven't asked any questions that weren't being discussed in great detail at both conferences.

I think you have one major misconception, which is that you're envisioning a relatively small ship. Any vehicle that takes longer than a human lifetime is going to be an extremely large ship; it has to be a self-sustaining high-tech society. Figuring out the minimum number of people to sustain that is an ongoing interesting question in sociology as well as post-World War III politics (there are people whose job it is to contemplate such unpleasant possibilities). The smallest number anyone's come up with is in the high five figures. The largest is in the low sevens. So, basically, you're sending a city. This obviates several of your issues.

Re: question four, that's wrong. There were several papers presented on this at the first DARPA conference. We do know how to do this, especially for a large vessel. It's not a problem.

As for question five, the answer is that you don't. The moment the ship passes beyond the instrumentality and authority of earth, which is measured in a few years, the people on board will do whatever the hell they want.

Again, reread the first column––you'll see that the purpose at this point is in good part to try to start figuring out answers to the questions you've asked (among many others). Because while a lot of the questions and answers will change over time, a lot won't. You have to start somewhere.

It's not your limited time and money that's being wasted. You may think they're being foolish, but you don't get to decide what is a waste of other people's time and money.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 03:34 PM

Dear rnewman,

What you suggest for a robotic probe isn't impossible, but there are far too few dollar signs in there!

In the timescale you propose, even let's say launching in 20 years instead of 10, you're constrained to “shovel-ready” technology. You can talk about scaling up engineering, but if you can't start drawing the blueprints today, forget it. That means it is possible to analyze this project with some assurance. On the ten year scale, the only thing that's possible is a photon sail. On the 20 year scale, you can possibly add in antimatter. (It's not quite shovel-ready, but if you decided it had to be…)

In my previous column on this subject, linked to near the beginning, figure 3 is a nice set of plots that's pertinent to your question.

The first, and unfortunate, answer is that you can scratch antimatter off the list. The stuff is simply too insanely expensive. For a 1 ton payload, the cost is in quadrillions of dollars.

So, we're back to photon sails. It is possible to build multi-stage photon sails that can not only decelerate at the destination end but even return to earth. Bob Forward figured all of that out 40 years ago. The economic disadvantage of photon sails is that almost your entire cost of the mission is electricity; photon sails are very inefficient at converting energy into thrust. That means there is little economy of scale. Your second, third, and fourth probes cost almost as much as the first one, because it's all operating expense.

You'd have to develop a substantial space-based power generation system to get electricity cheap enough and where you wanted it. That's not a negative; in fact that would be the kind of spinoff that DARPA would love to see. Even so, you'd probably be looking at several trillion per probe, and you'd have to assume you might lose a fair number of them before one survived; photon sails are not the most robust of structures.

But it is definitely one of the higher-grade options, because it involves far fewer uncertainties on the technological, economic, and managerial levels than many more ambitious possibilities.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 03:51 PM

Dear Ken,

Grin! No, nothing so obscure, just there are so many ways this can go wrong. While there are a handful of historical precedents for projects of this nature, they are so few and far between that they only constitute a proof of existence that something like this is even possible to do. They don't provide you with very good social engineering rules for pulling it off.

But new managerial and economic techniques are also spinoffs that DARPA is interested in. The Polaris submarine program (which was pre-DARPA) gave us PERT charts and the progenitors of all modern managerial tools. The race to the moon also required developing whole new sets of sociological and managerial tools which has since proven very useful.

~~~~

Dear Mike,

The “people vs. machine” question has been argued by many knowledgeable people, at great length, since the start of the space program. Actually, since the end of World War II. It's been debated in both the military and civilian space communities, as well as the governmental and private space communities.

My conclusion, after having read an awful lot of the stuff, is that the real and correct answer is “people do what they wanna do.” It's a lot like guns vs. butter economics. If you're convinced that machines make a lot more sense than people, you can produce excellent arguments in favor of that. If you're convinced the other way, you can produce excellent arguments in favor of that. And almost never do any of those excellent arguments change the minds of those with the opposite predilection. (Hmmm, there may be a nice OT column about this in the future…)

When you have a very well-defined and specific mission and goal, it is possible to do analyses of this question that will persuade people and change minds. But it has to be really, really specific (e.g., “going to Mars and doing geology” isn't anywhere near a narrow enough constraint).

So, I'm not going to try to make the case. Either way.

For what it's worth, there was a substantial working group at the last conference which was concerned with precisely this question. At the end of the conference, when they polled their members, it was pretty much an even split between machines and people. There was a small fraction who voted for “telepresence” but they were an insignificant minority.

The 100YSS Foundation has definitely NOT decided this matter. The way they're using the term “starship”, it could be anything from a 100 kg-payload flyby of another star to an entire city in space on a 500-year trip.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 04:06 PM

I think, given the successes both here on earth and in space of robotics, from sea floor to land surface to atmosphere to space, it's inevitable that robots will play a significant role in ongoing space exploration.

The only question is, what will the demand for canned apes be? Seems to me the longer the communications lag, the more important they become, until we start seeing the sort of AI that can handle completely new situations on its own. Which I don't expect any time soon; we don't know much about how to even work towards it. And the "one basket" argument for getting off the planet requires taking humans.

Posted by: David Dyer-Bennet | Thursday, 02 May 2013 at 08:40 PM

Dear DDB,

Real AI (not the magical kind that the Singularitarians keep imagining) is one of those “game changers” I alluded to in the previous column. The kind of thing that everybody at the conferences expects to happen in the next hundred years, but there's no agreement on what the game changer(s) will be. Just that something will come along demanding that all the plans be rethought. Which is another reason for putting off hard decisions.

Real AI, say something with an IQ of 70-80, radically changes plans for long generation ships in one pretty obvious way: you don't need anywhere as many people to sustain the high tech society. Since that's the limiting factor on how small you can make the ship, it's a pretty big change. It could be a couple of orders of magnitude.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Friday, 03 May 2013 at 07:54 PM

I take it that the starship will be unmanned. Makes me wonder if whoever is sending these UFO's had the same idea. As projects go this could be one of the most important one we ever undertake. Time for a real star trek

Posted by: dan@gabionstone | Wednesday, 08 May 2013 at 02:35 AM