The annual "X" column by Ctein

Seasonal greetings to you all. As is my tradition, my X-mas present to you is another "X" column that addresses one of the mysteries and wonders of the physical universe.

This time I'm going to take on the preeminent culture war of modern physics. No, not string theory—although all the spleen that's being spewed about over that topic does have a certain entertainment value. We even have a famous physicist raging that it has ruined an entire generation of scientists. Really, dude? I haven't read such pointlessly fiery rhetoric since the debates of the mid-1800s. I'm staying away from that one.

The question that splits the community and interests me is considerably more subtle and profound. I can state it in five words:

Is time a "process" or "content?"

I'll spend the rest of this column explaining just what the hell that sentence means.

The thing is, while we all experience time, we don't actually understand what we're experiencing. There is no physics, no experiment that really addresses this. We can measure time. Well, actually, spans of time...but we don't know what we're measuring them in.

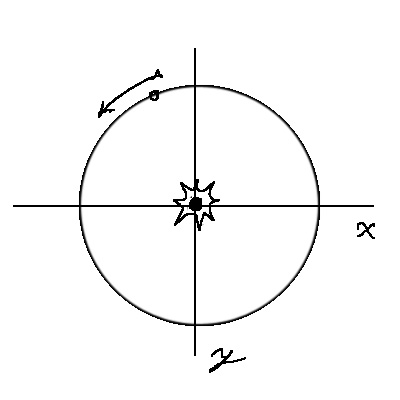

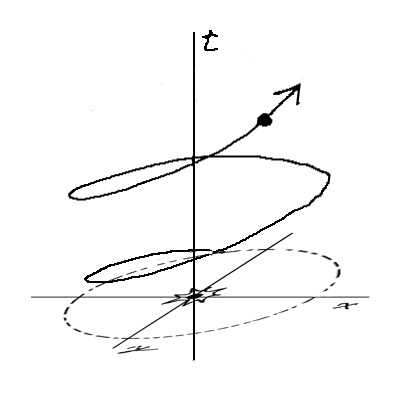

The common idea is that time is content, a real, physical thing. That's embodied in a lot of the way we talk about time. Einstein brought us the concept of space-time, which no one really disputes (at least, no one who should be taken seriously), conceptualizing it as another dimension, the so-called "fourth dimension." Bodies move not just through the three spatial dimensions but the fourth time dimension as well. A standard way of visualizing this is a "world line." Think of a planet in a circular orbit about a star, viz. figure 1. The star's at the center, and the planet goes round and round. But in this flatland world, if you draw in the "third dimension" of time, as in figure 2, you can describe that same path as a spiral, where the planet moves ever forward in time, around the star.

The concept of time as a real physicality is embodied in a lot of real physics and, more fancifully, the whole idea of time machines and traveling through time.

So, why don't we just accept this notion of time? It lets us make excellent physical predictions about the world, and, as I often say, data trumps theory. When the data seems to say that's the way it is, why even consider that it might not be?

Because there's one big problem with this notion of time as content. We can't observe the content! So far it has proven utterly impossible to experience any point in time except the present. We cannot move freely in time, like we can in the three spatial dimensions. Every attempt to come up with a real physical model that results in "travel through time" fails. It doesn't matter whether it's forward or backwards. We are stuck in time, moving forward at the rate of one second per second.

Now, the fact that every time machine theory has been disproven (or is, at least, unverified), so far, doesn't make it impossible. Some of them have come close. But that doesn't actually prove anything. The folks who designed perpetual motion machines came close. That doesn't mean that they are actually possible (hint: they're not). Close-but-no-cigar still means no cigar. So far, so far as we can tell, time travel is not possible. But we can't prove that.

(I should mention at this point that the kind of time travel that comes up in relativistic time dilation is a peculiar special case. It really involves the transformation of coordinates, it is not a free motion through time as a physical entity. It doesn't come into play in this debate, and I won't be discussing it further.)

And that's why there's a really, really big problem with the idea of time as content, because we have absolutely no idea, no physical model that can explain why we can't access other parts of the content than "now." The simplest and most satisfying explanation for that is that the reason we can't is because they aren't there. There are no other parts to time than now. Time is a process, the evolution of the universe second by second. It's a little like the universe is a great big grandfather clock, and the pendulum swings and the gears go tick tick tick, marking the passage of time. But that's just what the clock does; the clock is not time.

Much of modern physics incorporates this notion of time, too. A lot of quantum mechanics doesn't include time explicitly—it's something you apply to see how a wave state changes. Time is that second-by-second progression of physicality. There isn't really anything before now or after now. It is entirely now.

So, why is the debate so hot and heavy and laden with florid rhetoric. Because, not to put a fine point on it, this is philosophy, not really physics. Not yet. Both perspectives are equally attractive (or unattractive); the appeal of one or the other defaults back to an unstated sense of what "obviously makes sense" about the nature of reality. Once you buy into the axiom, the rest follows logically. But you have to buy into the axiom, and if two different philosophers buy into two different axioms, well, then there's no meeting of minds.

It is a wonderful puzzle and a profound question: What is the nature of time? Everyone's got an opinion, and none of us really have a clue.

Ctein

Physicist Ctein dabbles in photography and/or photographer Ctein dabbles in physics. We are not quite sure which is the correct philosophical model; but it's always fun to go with the flow column (tick) by column (tock).

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Erik Petersson: "This is an old problem. In the fifth century Augustine of Hippo said: 'For what is time? Who can easily and briefly explain it? Who even in thought can comprehend it, even to the pronouncing of a word concerning it? But what in speaking do we refer to more familiarly and knowingly than time? And certainly we understand when we speak of it; we understand also when we hear it spoken of by another. What, then, is time? If no one ask of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not. Yet I say with confidence, that I know that if nothing passed away, there would not be past time; and if nothing were coming, there would not be future time; and if nothing were, there would not be present time. Those two times, therefore, past and future, how are they, when even the past now is not; and the future is not as yet? But should the present be always present, and should it not pass into time past, time truly it could not be, but eternity. If, then, time present—if it be time—only comes into existence because it passes into time past, how do we say that even this is, whose cause of being is that it shall not be—namely, so that we cannot truly say that time is, unless because it tends not to be?'"

_files/patreon-2.gif)

Debating the time issue is really debating the free will issue. If time is not linear then we have no free will. Thus the hot and heavy debate.

Posted by: David Howard | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 04:05 PM

Something to keep in mind is that our perception of time is - to some degree - an illusion generated by our brain. See the "stopped clock illusion". We have this idea, this feeling, that we experience life as a constant high definition surround-sound movie, and that is simply not true in any meaningful way. Our brain is constantly generating it, inventing stuff and editing our short term memory as necessary to fill in the gaps.

This is actually somewhat related to photography, since the way we actually experience a photograph is somewhat different from the way we think we experience it.

Posted by: Andrew Molitor | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 04:08 PM

I know this column is not about relativistic time, but I am going to ask a relativistic question anyway: What does it mean to say that the universe began at such and such a time, or that at 10^-23 seconds after the beginning of time such and such a thing happened? After all, the universe was at near-infinite density then, and we know (or believe) that time slows down in a strong gravitational field. So what time was it really?

Posted by: Chuck Holst | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 05:21 PM

Been trying to avoid thinking about this very issue since my right knee started CLICKING, chronically.

Posted by: David Refffrum | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 06:46 PM

I'm no physicist (unless stoically enduring physics 101 grants me some status), but I think of time as a function of the entropy of the universe. There is only "now" because the universe has only its current state. When that state changes, we ultimately (I'll tiptoe past how we become aware of the changes) see in as the progression of time. The past is only our memory of previous states and the future doesn't yet exist. And, of course, the direction of time is the increase in entropy, in the accumulation of greater disorder in the universe.

Posted by: Dale Villeponteaux | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 06:54 PM

As human beings we have a linear experience of time and as we pass through we exchange it for memories. The closest I get to time travel is watching Doctor Who where I see that it causes all sorts of trouble and striffe, so its probably best left as a theoretical concept and the stuff of entertainment.

Posted by: Paul Amyes | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 07:02 PM

Dear Dave,

Ummm, I think you're misunderstanding the question. Whether time is process or content has no effect on the question of "free will" (regardless of what one means by that-- it means different things to different philosophers). Neither conceptual model of time requires it to be deterministic. You can make completely equivalent assumptions in either model (if you couldn't, well, that'd be a clear path for physicists to try to decide between them). Determinism? Not a distinguishing quality.

Maybe I can make the concept of time as a process clearer with another picture. This is comparable to figure 2, but from the perspective of time as a process:

In figure 2, the vertical T axis corresponded to a real physical dimension, not with the same properties as X and Y but with as much reality as it has. In other words, there's a “volume” of three-dimensional space-time there. We only directly perceive and can maneuver within the two-dimensional spatial slice, but the third dimension has reality nonetheless.

In the “time as process” point of view, shown in above figure, that third dimension doesn't have a real existence in the “past” and “future.” All that really physically exists is the X-Y plane; that's the entire tangible universe. You can think of that plane as moving forward through time (as indicated by the vertical arrows in the corners), if you like. I'm showing it that way for the convenience of visualization; as I said in the main article, we don't really know HOW time works. The important thing to come away with from this is that the only moment of time that actually exists along the T axis is the one that is in that plane, the moment of "now," which keeps moving forward at the rate of one second per second.

But whether time, be it process or content is deterministic, linear, or whatever, those are entirely other questions.

Hope I did better this time trying to explain a rather difficult idea

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 07:35 PM

The average non-scientist joe (I include myself) will tell you that time is nothing more than an arbitrary measurement of an object's movement in relation to other objects. If there is only one object in the universe, there is no time (and it's pretty boring too). I'm sure there's a lot more to it, but that's what my brain says at the ignorant hunch level.

Posted by: John Krumm | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 07:51 PM

I'm guessing , but you're going to need a wwwiiiid-angle on this one :-). For a non-physicist , the "time as a process" seems somewhat understandable, thanks for the enlightenment.

Posted by: Marc Saylor | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 08:02 PM

I'm not sure we can really ignore the problems for both concepts of time introduced by the tachyon and quantum entanglement. Both structures are in trouble if the limnit value of C (light speed) is called into question. Is a puzzlement....

Posted by: rnewman | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 08:41 PM

The problem with time as a "process" is that you're just shifting away the issue. For a process to happen, you need time, i.e. you're explaining time within the universe by a process happening to the universe, which in itself requires time (or meta-time, if you will).

Also, if time is a process, there's no reason why it should happen in the order we perceive time. As far as we know, for example, the laws of nature are reversible, so time could proceed from the future to the past, yet we'd still perceive it as proceeding from past to future. It might even randomly stop, reverse directions, change speed, etc.

Posted by: Mark Probst | Friday, 27 December 2013 at 09:07 PM

"So far it has proven utterly impossible to experience any point in time except the present."

Not entirely impossible...

http://reciprocity-failure.blogspot.com/2008/10/deja-vu.html

Posted by: Stan B. | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 12:46 AM

I know next to nothing about quantum physics except for having read a few popular books on the subject, but I remember reading about the phenomena of "quantum entanglement" ("spooky action at a distance"). At the time I remember thinking that it was, in a way, a physical state of "time" (or as you call it, "time as content"), that could be observed, albeit, in time, but which was distinct from the common experience of durational time. Any thoughts (that don't require a degree in physics to understand)? Did I completely misinterpret the whole entanglement thing?

cfw

Posted by: carl frederick | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 06:28 AM

The way we perceive time is a brain function, since the brain operates on the same physical level as everything else. It registers changes in state and, to an extent, responds to them, actions which are also state changes in the brain itself. Stimulus, response.

But the sense of time is an illusion brought about by the brain's ability to remember previous states and to imagine future ones.

Memory gives us the ability to retain elements of past states, albeit in a largely illusory and faulty internal storage mechanism that can at best be imperfectly recalled. No matter, the illusion that the past was real, a physical thing that we could taste and see and hear, exists.

Similarly we have the capacity to imagine and predict what may yet happen, even more imperfectly but again in a way no less real.

But neither memory nor imagination are real. They are simply a brain function endowed by evolution that helps us become better at dealing with the now on a level greater than the merely instinctual.

When we talk about time, we are really talking about change. Time is merely our experiential way of conceptualising change. Similarly we can travel in time, in a sense, by recalling a past event or imagining a future one. The only reason we cannot change it is because we cannot unravel the changes that have occurred in the meantime, though we can to some extent influence those that occur in the future.

That, in a real sense, is time travel.

Posted by: Steve Jacob | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 06:38 AM

Time is a creation of memory.

Posted by: ben ng | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 06:38 AM

I had this idea for a sci-fi story based on temporal interpolation. At some future date, the authorities discover a way to interpolate events in time to solve crime. They take pictures of EVERYTHING every 5 minutes, say, then determine who robbed a bank using algorithms that interpolate events to the intermediate time at which the bank was robbed. The algorithms are subject to error, of course, and I imagined a story where some poor sap was convicted of robbing a bank in error, but he can't prove he didn't rob it without examining the data and algorithms in detail, but the authorities don't want to give that info away.

Who do I send the synopsis to? :)

Posted by: Robert Roaldi | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 06:41 AM

Ctein, time you bought a new pen ...

On a more serious note; I have always preferred Aldous Huxley's definition, reflected in his work The Doors of Perception. When asked what he thought of time, he replied: "There's a lot of it about".

Posted by: Michael Martin-Morgan | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 07:28 AM

I think David Howard is saying that if time isn't linear and it's somehow possible to jump backwards and forwards then the "time traveller" might be able to influence events for a third party that is independent of their free will.

At least, that was what I took from his comment.

Posted by: Sevad | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 07:33 AM

The "Now" is all there ever is. I like your illustrations. (t=Now)

Posted by: darr | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 07:50 AM

When do we get to see the Camera of the Year? Gotta try to keep priorities in line.

Posted by: John Myers | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 10:42 AM

If your having a lot of fun on Saturday night time goes fast. If your waiting for 5pm on Friday time goes slow. It is relative to what you are doing. Therefore time is relativistic.

Posted by: Ken Brayton | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 10:48 AM

Very interesting stuff, as I've just started reading the Smithsonian Visual Guide to the Universe that was under the tree. I've long known of the concept of the content view of time as an infinite series of "parallel universes" from many sci-fi stories. (This ties into David's comment about "free will" ... if there is a future that includes us, then is our own future predetermined ? Is every action I will take something I've already done in the future ?)

And I think I've intuitively grasped the process idea, without ever thinking of it in the terms you've laid out here. But now after reading your thoughts/questions on time as a dimension, it makes me wonder more about the content/parallel universes concepts. We have three dimensions in space and we can only be in on place at a time. If we were over there and now we're over here, if we wanted to move back over there, we'd no longer be over here ! We can view "over there" where we were, but we're no longer there. If time were a fourth dimension, if we could look back in time (or forward) would we really find ourselves, as is popular in sci-fi ? Can we exist in two "places" in this dimension at once, a younger self and an older ? Or would we find it empty, because we'd already moved through that point in time ? Or ... weirder still ... would we find something totally alien there ? Something following us through time just as somebody else can stand where we just stood a minute ago ? And if that's the case, and we can not only fail to find ourselves in the past, because we've already moved through it, but also fail to find all the mass in our universe, then would these pasts and futures be indistinguishable from the sci-fi view of parallel universes in which people can travel to universes in which nothing is the same as in ours ? Or would it all be emptiness ?

I love the concept that when we look at distant objects, we're seeing what happened in the past. If we had a sufficiently high powered telescope, we might watch a civilization die on a planet 100 million years ago and have no way of knowing what's there today. But we're not seeing into the past; we're only seeing light traveling through the universe today, so that doesn't argue for the content model.

But the more I think about it and the more I put these questions down, it seems that if time truly were another dimension, that we should be able to move through it differently. Time as a process makes more sense to my brain, even if time as content makes for better stories.

Happy Arbitrary Point in the Process Marked by a New Year On the Calendar !

Posted by: Dennis | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 10:52 AM

Okay, I thought of one more silly thing this morning when I woke up. Time is how we perceive existence, or being. It IS existence. The reason we cant time travel is that there is only one state of being (your now). And as someone else said, our perception of time comes from memory (the past) and our imagination (the future) enhanced by our scientific ability to predict and prove. Okay, time to go take some pictures.

Posted by: John Krumm | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 11:45 AM

At Robert R... Anybody but the NSA

Posted by: Terry Letton | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 12:12 PM

Dear Mark Probst, cfw, & rnewman,

You all caught on to the main reason why this is a hot and heavy philosophical debate, which is that it doesn't really SOLVE any of the problems. It makes some minor ones go away, like the conceptual puzzlement of why we don't seem to be able to build a time machine, but neither conceptualization answers any of the important questions of physics more or better than the other. Just differently.

Which removes it from physicists comparing data and into the realm of argumentation.

So far the tachyon doesn't exist, so we ignore it. But quantum entanglement is a big deal. It's believed to occur instantaneously; it's been measured to “propagate” faster than 10,000 times C. Because it doesn't allow the propagation of **information** at greater than C, it doesn't mess with the measurement of time–– we can only measure durations of time by conveying information. But it's more than a bit of a puzzle.

Similarly, reversibility (specifically, charge-parity-time reversibility) is another matter that isn't resolved by this. Whether time is process or content, we don't have a really satisfactory reason why it appears to flow unidirectionally. There's a statistical argument based on entropy, but it's not very satisfactory for something that seems so fundamental, and ultimately it turns out to be a circular argument. Similarly, it's been proposed that this is just something that gets “set” when a universe is formed, one of the many properties that freezes out of the super-continuum. The idea being that there is no preferred direction for the flow of time, but much like a spinning coin, when it settles down it has to come up definitively heads or tails.

This may, in fact, turn out to be exactly how it works; there are lots of properties of the universe that developed this way, like the four fundamental forces (it's called symmetry breaking). But physicists really hate defaulting to a “it just happens to be that way” explanation without any physical understanding of WHY it just happens to be that way.

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 03:36 PM

Dear StanB,

Fair enough! That was sloppy writing on my part. There are many reports out there of subjective, non-reproducible phenomena that are not time-restricted.

The problem is that science (so far as we know how to do it) is incapable of working with subjective, non-reproducible phenomena. They simply fall outside its purview, which means they're outside the scope of this column.

Technically that makes my sentence correct, but I could've written it more expansively to make it clear we're talking about measurable science here, not the totality of human thought.

I just dash this crap off, ya know… [grin, but with a certain grain of truth]

~~~~

Dear Robert R,

If you are a well-established author, e-mail some editor you know and say, “Hey, I've got a story idea I'd like to toss at you, noodle it about a bit before I try writing it up. You got some time?”

If you're not, just write the story and submit it. Nobody buys on outlines from unknowns.

As my friend Pamela Dean once wrote, "I don't think editors are any crueller than the general populace, they just have more opportunity."

So true, so true.

~~~~

Dear Michael M-M,

Turns out it's really, really hard for me to draw spirals on a tablet! Dang!

pax \ Ctein

[ Please excuse any word-salad. MacSpeech in training! ]

======================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

======================================

Posted by: ctein | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 03:48 PM

Agree, time is process. My 2¢. I still remember the day when the question, "what is time?" got stuck in my head. I was probably 11 or 12. My conclusion, time isn't a thing. It's a consequence of action or change. No change, no time. And by "change" I mean any change, even at the quantum level. Thought experiment: Imagine a one particle universe. Nothing else. *Nothing.* For simplicity, imagine our particle is a simple (indivisible) Newtonian particle. There is no time in that universe. Motion, energy, temperature, etc. are impossible without a relative reference. Time is a measure of action/change between events. The action/change being measured may be the ticks of a clock, the vibrations of a crystal, or the count of orbits of a planet.

Posted by: paul kramarchyk | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 03:57 PM

Ctein says..." I can state it in FIVE words:

Is time a "process" or "content?"

Physics aside, a math major would disagree with the above assertion.

Posted by: Jeff | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 05:13 PM

"The 'Now' is all there ever is." (@darr)

Or there is no "Now" at all: the "Now" we experience is our brain's processing of the stimuli presented to it. There is always a gap between the signal and its processing. The present is therefore always retrospective. And the very moment we move one level of abstraction away, and we start to consider it, think about it or analyse it, we are already working with a memory. I think you could rather say the past is all we ever know.

Or as ben ng says much more pithily above, "Time is a creation of memory."

To bring this around to photography, like the changes in our brains, photographs are a material, fragmentary, and selective record of the transit of a present into the past. There is never a "Now" in the photograph, always only a past.

A good illustration, Ctein's moving plane also feels appropriate. There is nothing in the "Now" there either. Just the about to happen and the already happened. And it's less circuitous than Augustine. (And as a bonus, now I know where my axioms are lurking.)

Posted by: Carson Harding | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 06:17 PM

Time is what the railways make their tables out of to run their trains on.

Posted by: RobG | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 10:00 PM

"Can we really claim to know anything about the nature of the universe if we don't know the properties, or even the nature, of 90% of its material?" --Prof. Ivan King

Posted by: Stan B. | Saturday, 28 December 2013 at 10:56 PM

Dear Richard,

Personally, I think you're onto something.

Vis:

http://theonlinephotographer.typepad.com/the_online_photographer/2011/08/cteins-200th.html

time could turn out to be another one of those "elementals."

Certainly our understanding of it sounds suspiciously like that.

No data to back that up, just a gut feeling.

~~~~~

Dear StanB,

Happens I wrote about that about three years back. Following the links off of the 200th column link, above.

The answer to Ivan's question is really very simple. Yes. Of course we can; we know a great deal. What we cannot do is claim to know everything. Possibly even most things. But *any*thing? Most certainly.

pax / Ctein

==========================================

-- Ctein's Online Gallery http://ctein.com

-- Digital Restorations http://photo-repair.com

==========================================

Posted by: ctein | Sunday, 29 December 2013 at 02:53 AM

Jeff, a math major might -- but actually doing simple arithmetic, or counting to 5, aren't necessarily part of a math major's skill set (I speak from personal experience here).

Posted by: David Dyer-Bennet | Sunday, 29 December 2013 at 10:48 AM

"Time" is just the eternal present cloaked in the illusion that there is a future and there is a past. Time is man-made and not a creation of nature.

Enlightenment is simply the process of living in the eternal moment where man-made time does not exist. Most humans are not enlightened so time seems to exist, but time is illusory.

Posted by: Jeff1000 | Sunday, 29 December 2013 at 11:11 AM

Ctein,

The tachyon is a predicted - and doubted -but not detected 'particle', much as the Higgs boson was until recently. And quantum entanglement has recently generated discussion of 'quantum wormholes'. Could science fiction be predicting future physics this time?

Posted by: rnewman | Monday, 30 December 2013 at 01:03 PM

Dear rnewman,

There are big differences between the tachyon and the Higgs particle. The tachyon is unnecessary. It's a possible consequence of the math, like magnetic monopoles, in that it is not prohibited. But it need not exist for physics to be complete, and its existence would create substantial problems. It was doubted from Day 1, it's just that it is not disprovable.

So, although it would be really cool if it were to turn up, until evidence for it actually surfaces, it properly gets ignored.

The Higgs particle, on the other hand, is a necessary part of the Standard Model. It was not doubted. It was hoped, kinda, that it wouldn't turn out to be as expected, because then there'd be a lot of cool new physics to play with, but that's not the same thing.

Unfortunately, no such luck. Durn.

Science fiction never "predicts" the future. Science fiction is a random roll of the dice of the imagination. Sometimes the numbers that you roll just happen to agree with what the future brings. But it's monkeys and typewriters. Lots and lots of monkeys. So says one of the monkeys (vbg). ook ook.

pax / Ctein

Posted by: ctein | Monday, 30 December 2013 at 11:49 PM

Fascinating discussion of an enduring (and evanescent) problem. The big questions about time that offer themselves to me personally, though, are simply:

"How much more of it do I have left?"

and

"What am I to do with it?"

Posted by: Thomas Turnbull | Wednesday, 01 January 2014 at 03:40 AM